How a once-reluctant viewer became a loyal fan

By Frank Rizzo

As the final episode of the TV series “Schitt’s Creek” neared, I knew I didn’t want to say goodbye to these characters I had come to love – and to the fictional town they called home.

As the final episode of the TV series “Schitt’s Creek” neared, I knew I didn’t want to say goodbye to these characters I had come to love – and to the fictional town they called home.

But in my heart, I knew it was time to go.

Over six seasons on POP TV, and then available more widely on Netflix, this landmark series slowly built an audience, then a following, and finally, in the end, became a phenom.

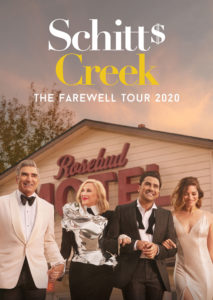

Among the earliest of fans who spread the word about the series were those in the LGBTQ community who embraced the extravagance of Moira Rose as a new gay icon, as well as the wide range of characters from the series. “Schitt’s Creek” theme parties started popping up at gay bars across the country, including in Connecticut at the Trevi Lounge in Fairfield. A tour of the cast members was scheduled for the Mohegan Sun Arena before it was postponed earlier this year, due to the Covid-19 pandemic.

This series with a decidedly queer aesthetic just got better, deeper, and surprisingly moving as it went from season to season, following the lack of fortunes of the once-filthy-rich Rose family.

In the first minutes of the premiere episode, federal agents swooped in the family mansion, removing all their assets – the result of an unscrupulous business manager. They were left with only some personal belongings and the deed to a remote small town with the questionable name that the patriarch bought for his son as a joke.

It was there that the Roses retreated, living in two adjoining rooms in a cheap motel at the edge of a town they called upon arrival “disgusting and gruesome.” But first impressions aren’t always the best.

Indeed, I resisted viewing the series for a long time, despite being an admirer of the brilliant Catherine O’Hara and Eugene Levy of “SCTV” fame and the classic comedy films that Levy co-wrote with Christopher Guest that also featured O’Hara (“Waiting for Guffman,” “A Mighty Wind,” “Best in Show”).

Perhaps I was put off by the cheap-joke title and seemingly shooting-fish-in-a-barrel premise where I surmised it was “Arrested Development” meets “Green Acres.”

But eventually I started watching and boy, was I wrong. Yes, the Roses were horrifyingly self-involved, staggeringly oblivious, and pretentious to the max. Leading the quartet were Levy as entrepreneur and half-billionaire Johnny Rose and his wife and soap star Moira, played by O’Hara. Then there was the next generation: jet-set daughter Alexis played by Annie Murphy and spoiled, elitist and pansexual son David played by Daniel Levy, who also created the series with his father.

“Schitt’s Creek,” as it turned out, wasn’t what I expected – and neither were the Roses or the town.

When Daniel Levy said Schitt’s Creek was “in the middle of nowhere,” he was right, on multiple counts. It was never explained exactly where the town was – what state, or even what country, though Canada would be a logical guess considering the roots of the show. But “nowhere” took on another meaning. This is a town that could exist in a better world, where the outsider is not only tolerated but welcomed; where sexuality and gender flow as freely as the wine, where acceptance is a matter of fact, not a special episode.

Without preaching, the series showed – mainly through the journey of David, but also, ever-so-subtly, with everyone – a modern queer sensibility like no other.

From the first season, a coded conversation about sexuality between David and Stevie, the motel desk clerk (played with a sly, wry deadpan by Emily Hampshire) became an instant classic. Soon there were T-shirts at Gay Pride events that read: “The wine and not the label.”

But it was also David’s parents’ responses to their son’s sexual fluidity that was endearing. A scene between Roland and Johnny, both stoned at a backyard luau, was also one of the sweetest moments of the series:

Johnny: My son is pansexual.

Roland: I’ve heard of that. That’s the cookware fetish?

Johnny: No, he loves everyone: men, women, women who become men, men who become women.

Roland: Well, you know, Johnny, when it comes to matters of the heart, we can’t tell our kids who to love.

Or the scene where schoolteacher Jocelyn asks David to counsel a gay high school boy whom she feels is not fitting in. The scene between David and Connor (Matthew Tissi) offered a peek into a different Gen Z perspective than what David was expecting. “Why would I talk to you?” asks a snippy, self-possessed Connor. “Look at you. Look at your pants…. Let me tell you what my problem is. I’m a 16-year-old gay kid living in a town that makes me want to throw up. This issue isn’t me not fitting in. It’s me not wanting to fit in.”

The kicker is that Connor ended up counseling David on his recent friends-with-benefits relationship with Stevie: “Have you not seen the 42 films they made about it? It never works.”

But it was the slow-budding relationship between David and local man Patrick (the adorable Noah Reid) in the third season that made by this gay heart burst with joy. Patrick’s confession that it was the first time he had ever kissed a man before was met by the perfect, revealing response from David, saying though he’s kissed many men, as far as anything coming close to being real, it was his first time, too.

But the get-out-the-tissues moment was the episode when Patrick unexpectedly serenades David on acoustic guitar with an intimate version of Tina Turner’s “Simply the Best” in front of a store full of locals. Re-watching the scene, I was moved to tears yet again, not just by David’s verklempt reaction, but that of O’Hara’s Moira, touching her son tenderly on the arm, as if to silently bless the union. But it was also David’s gesture of apology to Patrick in a later episode – a fearless lip-synch to Turner’s “Simply the Best” – that finally liberated David from his protective shell, signaling that this relationship might just work.

But the get-out-the-tissues moment was the episode when Patrick unexpectedly serenades David on acoustic guitar with an intimate version of Tina Turner’s “Simply the Best” in front of a store full of locals. Re-watching the scene, I was moved to tears yet again, not just by David’s verklempt reaction, but that of O’Hara’s Moira, touching her son tenderly on the arm, as if to silently bless the union. But it was also David’s gesture of apology to Patrick in a later episode – a fearless lip-synch to Turner’s “Simply the Best” – that finally liberated David from his protective shell, signaling that this relationship might just work.

There were countless moment of LGBTQ bliss – and heterosexual, too, with dreamy love interests for Alexis (hunky Mutt and dreamy Ted). And the series finale, where David and Patrick marry, made for perfect and satisfying happy endings.

Hitting rock bottom, the Roses went to Schitt’s Creek without a figurative paddle and yet not only survived but, while still remaining their idiosyncratic selves, found their humanity – and a new sense of family.

More Stories

Broadway Review: Art

Fall Arts Preview: Emus, Foxes and Eric Clapton, Too

Diane DiMassa Book Event September 25