Yale’s Beinecke Library is home to a growing number of LGBTQ treasures

By Frank Rizzo / Photography by Tony Bacewicz

The archives of gay activist Larry Kramer, furniture of Gertrude Stein and Alice B. Toklas, diaries of photographer George Platt Lynes; the papers of writers such as David Rakoff, Langston Hughes, David Sedaris, David Leavitt – the works of some of the world’s leading LGBTQ figures – can be found among the collections gathered, preserved and available for researchers at Yale’s Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library.

More? How about papers and collections of writers Hart Crane, James Baldwin, Paula Vogel, W. Somerset Maugham, Thornton Wilder, Edmund White, and Oscar Wilde – and so many more LGBTQ figures?

This literary archival bonanza is in a solitary, glistening white jewel box of a building, tucked behind Woolsey Hall in a corner of Hewitt Quadrangle at 121 Wall St. in New Haven. It’s a building of contrasts. A fortress and a sanctuary. Physically modern yet spiritually eternal. It’s a building that from the plaza looks cool, opaque and intimidating. But enter through its revolving door and be bathed by a warm, golden glow from the wall’s translucent, veined marble, windowed throughout in its giant granite hexagonal grid.

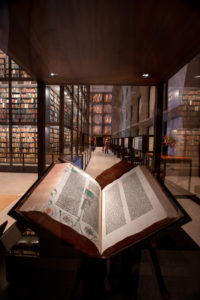

Its interior space is spare and spacious, yet its inner sanctum – a six-story, glass-enclosed tower of 180,000 books – is a jaw-dropping showstopper (and Instagram fave). If the tower acts as a cathedral of books, then its exhibition spaces on the surrounding two floors are like literary chapels, offering a more intimate look and private revelations. The building was designed by architect Gordon Bunshaft of Skidmore, Owings & Merrill, who also designed the Lyndon Baines Johnson Library and Museum in Austin, Tex.

If the Beinecke is a center of rich humanities scholarship, it is also a place for personal reflection, where one can sit on the mid-century furniture (designed by Florence Knoll and Marcel Breuer) and gaze at the titles on the bindings of the books in the tower. It’s a kind of communion between writers and readers through the ages, and the presence of a widening collection of LGBTQ figures among history’s greatest minds adds to the richness of it all.

The Beinecke’s director, Edwin C. Schroeder, enjoys watching the faces of new visitors as they enter through the building, seeing their eyes light up and soar upwards to the top of the stacks tower. More than 200,000 scholars, students, visitors and tourists came through the doors last year.

“You’ve walked into a space where books, writing, literature, and the human experience are front and center,” he says. “You know this is someplace special.”

Institutional changes

The most popular item sought at the Beinecke? The Voynich Manuscript – the mystifying, 15th or 16th Century cipher manuscript that has remained an enigma since it was donated in 1969. Its puzzling text (seemingly an encrypted language) and its bizarre illustrations have confounded scholars and fascinated the public for decades. The so-far unsolved manuscript is the subject of documentaries, as well as young adult and graphic novels.

That manuscript, like so much of the Beinecke’s materials, is available online too. But those who want to delve deeper in scholarship, or just feel the talismanic power of seeing original source material, are also welcome, seven days a week, free of charge.

It was not always so. When the museum opened nearly 60 years ago, it was a temple for the privileged, seemingly exclusive and mysterious, a literary Skull & Bones.

“I would describe it as a men’s club. You had to be a senior scholar, a famous collector, a curator or a faculty member,” says Schroeder of those early days before Yale went co-ed and the fundamental nature of the institution evolved to be more inclusive. Even students were not actively encouraged to fully utilize the library. “The director famously pushed students out who seemed to be loitering on the mezzanine.”

For Schroeder, that was the long-ago past. Today’s mantra is access, in terms of student and scholar usage, as well as in welcoming the general public to view its exhibits.

“We went from two classrooms to seven now, where we can do nearly 600 classes a year serving students not just Yale but from Hopkins School and New Haven Promise,” says Schroeder.

Major renovations were made in 2016 after an 18-month closure which dramatically expanded its staff, and its teaching and archival capabilities.

Schroeder says as the massive card catalogue has made way for digitized access, the Beinecke has also become more efficient, able to locate needed materials from its building as well as the library’s shelving facility in Hamden, home to low-use, circulating books or the archival collections at the other colleges of Yale. (Looking for Cole Porter material? That’s at the School of Music — but the Beinecke can retrieve that collection for you.) More than one million volumes and several million manuscripts are available in total.

But unlike the centrally located Yale University Art Gallery and the Yale Center for British Art, the Beinecke’s site and formidable physicality is a challenge. “Unless you know the campus, you can’t get to us very easily, or at least, it’s not as obvious a building as others,” says Schroeder.

Exhibitions – always free – are also limited by the restrictions of the building’s design. Exhibition materials must be placed in the originally designed cases. While architecturally pleasing and suitable for limited interest more a half century ago, the size of the cases now confines what the curators can exhibit. The collections have grown to include a wide range of materials – from ephemera to substantial physical items, such as a pair of petite fireside chairs owned by Gertrude Stein and Alice B. Toklas, with upholstery designed and painted by Pablo Picasso.

“There is so much here, and we want to show the diversity of what we have,” says Schroeder.

Vast materials

Anchoring both sides of the mezzanine are two massive books that are on permanent display: one of the 48 extant copies of the Gutenberg Bible and the “Double Elephant Portfolio” of John J. Audubon’s “Birds of America” (1827-1838). One the main floor is the pen that Abraham Lincoln used to sign the Emancipation Proclamation.

Anchoring both sides of the mezzanine are two massive books that are on permanent display: one of the 48 extant copies of the Gutenberg Bible and the “Double Elephant Portfolio” of John J. Audubon’s “Birds of America” (1827-1838). One the main floor is the pen that Abraham Lincoln used to sign the Emancipation Proclamation.

Stored below are ancient papyri, medieval manuscripts, personal papers, photographs, drafts of books, handwritten letters, and assorted personal items from writers, poets and cultural figures, adding up to a who’s who in the arts and humanities over the centuries of civilization.

The Beinecke includes works or archives of J.M. Barrie, Rachel Carson, Joseph Conrad, Richard Wright, Charles Dickens, Alexis de Tocqueville, George Eliot, Thomas Hardy, Robert Lewis, costumer Irene Sharaff, actor Marian Seldes, Robert Louis Stevenson, James Joyce, Rebecca West, Rudyard Kipling, D.H. Lawrence, Doris Lessing, Eugene O’Neill Jr., Thomas Mann, set designer Ming Cho Lee, Lillian Hellman, Edith Wharton, Ezra Pound, and the just-acquired David Sedaris.

To clarify the mythology surrounding the scenario of a fire in the central book tower (not accessible to the public): Yes, the glass-enclosed stacks can be flooded with a mix of Halon 1301 and INERGEN fire suppression gas if fire detectors are triggered. But not until everyone is out and all persons are accounted for.

What to collect?

So how does the Beinecke decide what to collect, given its vast resources and stellar reputation?

“Our idea of collecting is that we build on existing strengths,” says Timothy Young, curator of modern books and manuscripts for the last 28 years.

“The collections in Beinecke Library have always contained the voices of LGBTQ writers and artists,” he says. “A focus of the past several decades has been to recognize those voices by noting their presence and impact on the creative accomplishments we document. We continue to acquire books and archives that help our researchers and visitors see the amazingly broad array of work done by individuals and groups working – in gestures from subtle to explicit – on gender, sexuality, and identity.”

Young sees the Beinecke now going well beyond being “a monument to colonialization and patriarchy.” Young takes an expansionist view of American Studies beyond the high-profile names of generations past, to seek out those from backgrounds that are more diverse than the western European works that formed the foundation of the Beinecke.

“We are also interested in those who potentially influenced a figure to tell that broader story and to see how that plays out.”

And as more personal stories are gleaned from the increasingly diverse collections, their relevance to a broader audience becomes ever more evident. “We might seem to be in an ivory tower, but these collections might have something to say about your daily life,” says Young.

New technology in a fast-moving age and the ways that people – especially literary figures – communicate are on-going challenges.

“We are collecting more material that is digital in nature,” says Young. “And we struggle with how to collect social media and websites.”

New exhibit on travel

The next exhibit at the Beinecke was to have been “Road Show: Travel Papers in American Literature,” by Nancy Kuhl, curator of poetry in the Yale Collection of American Literature. (The show was put on hold during the pandemic shutdown.)

That exhibit features material from Zora Neale Hurston, Gertrude Stein, Edith Wharton, F. Scott Fitzgerald, Richard Wright, Gwendolyn Bennett, Saul Steinberg, Truman Capote, Annie Dillard, and many more literary and cultural figures.

“It’s not an exhibition exclusively about writers being ‘on the road’ or novels about travel,” says Kuhl. “It’s more about how a writer’s experience in traveling results in a great work of art. A writer’s archive is not something outside of time and place. It’s specific to a culture and a community so all of these [materials on exhibit], twisted into a certain light, tell us something about that culture. What kinds of travel do writers undertake, far beyond their creative lives, far beyond what we can see on the surface of a novel? How do their movements in the world impact their lives, their families, their work?”

The exhibit, for example, will feature evidence of F. Scott Fitzgerald traveling in Europe, meeting American friends and expatriates Gerald and Sara Murphy in the 1920s, “and we see how that traveling experience 15 years later becomes “Tender Is the Night.”

Among the travel items featured are about a dozen passports that belonged to cultural figures of the past century.

“What can be more intimate than a piece of identification that’s been in your front pocket during the course of your travels?” asks Kuhl.

Other materials offer a darker view of travel. There’s also the “Green-Book,” a traveling guide for African Americans that was the basis of the Oscar-winning film of the same name.

And there’s a business card from a hotel in Ohio that features a picture of its black owner. “It reflects the complexities of traveling as an African-American in this country before the Civil Rights Act – and even after. The significance of a person putting his picture on a business card identifies the hotel as a place that’s safe for a whole community of travelers.”

Other items in the exhibit include whimsical maps by artist Saul Steinberg; traveling material by Langston Hughes; and postcards from Ernest Hemingway.

“One of the things this institution is about,” says Kuhl, “is exciting students’ minds and engaging them in whatever way, whatever might spark a spiritual connection, whatever might lead a student to do more rigorous research.”

More Stories

Off-Broadway Review: Trophy Boys

Broadway Preview: Lewis Flinn’s Cabaret

Off-Broadway Revew: The Imaginary Invalid