LGBTQ dads-to-be travel unique journeys to parenthood

By Lisa Backus

As a gay man living with HIV, Brian Rosenberg presumed in the 1990s that he would never become a father.

But thanks to advances in medicine and a shared desire to start a family, more than a decade later, Rosenberg and his then partner (now husband), Ferd van Gameren, found themselves racing through a buybuy BABY store in 2009, in preparation for bringing their newborn son Levi home from the hospital.

“We had no family near us to help advise us. As first-time dads, we were bringing home a newborn baby and we had nothing,” Rosenberg says. “The staff helped us grab everything we would need. But what we noticed was that a majority of stuff was geared toward moms. We were like, ‘Are we not supposed to be buying this stuff?’”

That was the tip of the iceberg in terms of their enlightening moments as gay dads, the two quickly realized. From the pediatrician to the pre-school, Rosenberg says, they continually had to explain their family situation.

After the birth of their twin daughters Ella and Sadie through surrogacy 17 months later, Rosenberg decided that he wanted to connect with other gay dads and offer gay, bi, and trans men hope and a way to become parents themselves.

What started as a labor of love, Rosenberg’s Boston-based organization Gays With Kids has become one of the world’s largest online communities of gay, bi, and trans parents and prospective parents, offering information and support on family building options including surrogacy, adoption, and foster care.

“I knew I wasn’t the only gay dad out there,” the 55-year-old Rosenberg says.

The Gays With Kids website, gayswithkids.com, and social media accounts on Facebook and Instagram tell the stories of hundreds of gay men who successfully entered parenthood, while explaining the joys and pitfalls that came along the way.

Equally as important, Rosenberg provides weekly webinars with step-by-step instructions and an overview of each of the paths to fatherhood typically available to queer men, from in vitro fertilization and surrogacy to foster care and adoption, the potential costs, and amount of time and paperwork each route can take.

The organization has 250,000 followers on social media, with the website garnering 140,000 to 175,000 visits a month.

Gays With Kids also works with fertility clinics and surrogacy, adoption, and foster care agencies who are supportive of LGBTQ parenthood, providing information on which family-building organizations queer men can access for help.

“We don’t come to fatherhood by accident,” Rosenberg says. “A lot goes into us becoming parents.”

The Journey to Fatherhood

In Vitro Fertilization and surrogacy offer gay men a chance to have a biological connection to their children. The process requires the implantation of an embryo, usually created with the sperm of one or both prospective fathers and an egg from a surrogate or other female donor. The cost ranges from $170,000 to $250,000 and includes a fee for the surrogate mother who will carry the baby to term.

This route usually requires gay men to seek the help of a surrogacy agency which arranges for a surrogate. It can take up to two years to become parents, including the three to five months required to match a surrogate and create an embryo, according to Gays With Kids.

Foster care and adoption are also viable options and require fewer financial resources in about the same timeframe. But the process can be a rollercoaster, Rosenberg warns, especially if biological parents or other family members ultimately choose to keep or be reunited with their child.

Agency adoptions cost $20,500 to $63,000, while independent adoptions range from $18,500 to $47,000. International adoptions cost $28,500 to $54,500 and can take anywhere from one to five years. Foster care-to-adoption is the least expensive proposition at $1,800 to $4,500 and takes the least amount of time – an average of six to nine months.

As part of each option, a home study will be done that involves a case worker, legal paperwork and, in some cases, training.

In addition to financial challenges, there are also legal stumbling blocks. Some states have laws allowing adoption and foster agencies to decline to work with members of the LGBTQ community on the basis of religious beliefs, and not all states allow surrogacy.

Marital status can be heavily connected to the right to be listed as a parent entitled to make medical and schooling decisions for a child, and may also have immigration implications.

At the time Rosenberg and van Gameren became first-time parents, van Gameren had been living in the U.S. legally for several years using a tourist visa, which expired and needed to be renewed from outside the country every three months. Shortly after Levi’s birth, van Gameren was told he could no longer stay in the U.S. using the tourist visa. Rosenberg and van Gameren decided to move to Canada.

They got married in Toronto on their 20th anniversary (June 20, 2013), since Canada offered federal recognition of gay marriages. Several American states also recognized gay marriage at the time but the federal government did not. This meant that gay couples who married would only receive state benefits and not federal benefits such as marriage-based immigration rights.

After the U.S. Supreme Court ruling in favor of marriage equality in 2015, the couple moved back to the U.S. Since that time, they have not only continued to build their family but to help other LGBTQ couples do the same.

“For queer men, the journey to fatherhood is very often overwhelming and exhausting,” Rosenberg says. “What we’re trying to do is make it less so. We provide a lot of anecdotal stories of men who have already gone through the process. People can look at them and say, ‘They did it; there is no reason why I can’t do it.’”

Family Planning on the Rise

The support comes at a groundbreaking time for gay, bi and trans Millennials who, according to a 2019 national Family Equality Council survey, are now considering family building at about the same rate as non-LGBTQ Millennials, with 48% actively planning to grow their families compared to 55% of non-LGBTQ Millennials.

“What I think is amazing now is that when I talk to twenty-somethings, they know they are getting married and having kids,” says Dr. Mark Leondires, who specializes in reproductive endocrinology at his practice, Reproductive Medicine Associates of Connecticut. “In a matter of 30 years, the LGBTQ community feels safe to have a family. It’s heartening to me that the younger generation feels it’s possible.”

It’s a totally different mindset from when Leondires’ husband Greg Zola came out as gay decades ago and loved ones tried to dissuade him by saying he would likely never become a parent, he says.

“For 15 or 20 years that’s what I thought,” Zola says. “There was an attempt to try and change me; they said, ‘You’ll never be able to enjoy the experience of being a parent,’ and that’s not true.”

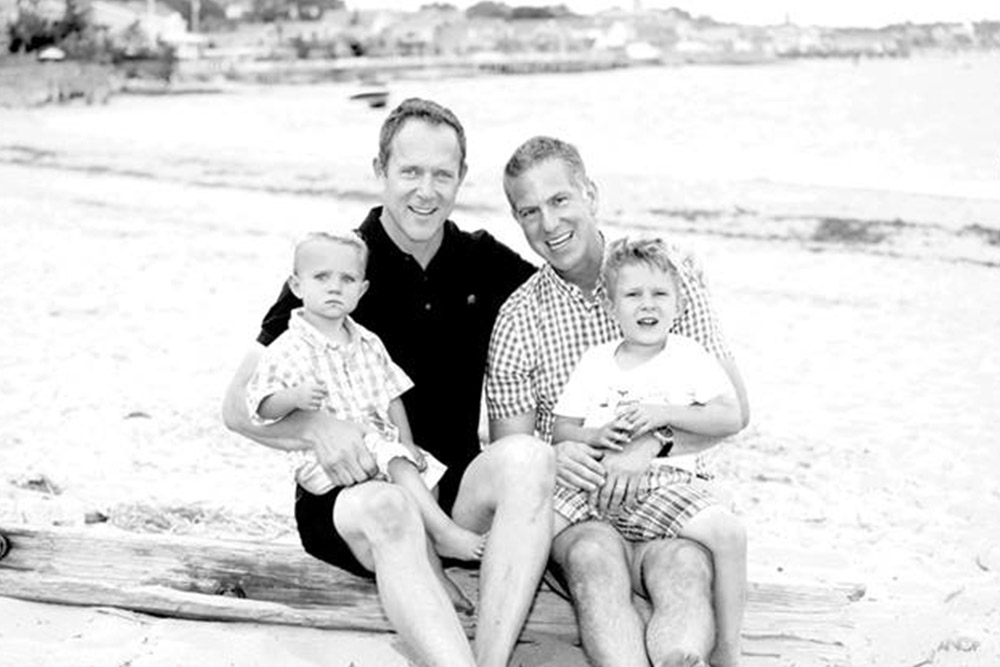

Leondires and Zola are raising sons Luke, age 9, and Owen, age 7, in their Westport home. It’s a lively time, as the boys consistently remain one step ahead of their parents, both say.

“One of the things that I don’t think anybody ever shares is that your kids keep getting smarter,” Leondires says. “Our boys tag team us continually.”

Their first surrogacy ended in miscarriage, the couple says. It was a heartbreak that Leondires credits with making him a better doctor. “I learned what it’s like to be on the patient’s side,” he says. “There were some powerful lessons from it.”

Leondires heads his clinic’s Gay Parents To Be program (gayparentstobe.com/about), which provides support to prospective gay parents considering or undergoing fertility treatments in the hopes of starting or expanding a family.

Leondires’ and Zola’s journey to parenthood includes their own mad dash in the hours before Owen was born. The couple was living in Connecticut but the couple’s surrogate had moved while pregnant to Washington state, where compensated surrogacy was not legal.

The original plan was to have the surrogate’s husband bring her to a hospital in nearby Idaho, which did allow compensated surrogacy, when she went into labor. But they all had to quickly form another plan when her water broke unexpectedly on a day that her children were sick.

Zola had been staying at a hotel across the street from the Idaho hospital, waiting for the big day to arrive. When the call from the surrogate came with unexpected news, he sped across the state line in a small rental car to Washington. On the 45-minute drive back to the hospital, as he was trying to drive at a more reasonable rate, “she starts having contractions in the car,” he recalls.

Compensated surrogacy is legal in 47 states, with New York recently joining the list – on February 15, 2021 – but laws differ by state. And while the surrogacy law that affected Zola and Leondires has since been overturned, there are still obstacles, legal and otherwise, to gay parenthood.

Just one example is a brief submitted by the Trump Administration to the U.S. Supreme Court in June 2020, supporting a religious nonprofit that is suing the City of Philadelphia on the grounds of religious freedom. The nonprofit, Catholic Social Services, runs a child welfare agency in that city and has been refusing to place foster and adoptive children with same-sex and other LGBTQ parents, in violation of Philadelphia’s non-discrimination ordinance. The federal Department of Justice argued that the city’s position reflects “unconstitutional hostility toward Catholic Social Services’ religious beliefs.” Arguments in the case were heard in November; a decision is still pending.

“There are 400,000 children in the Unites States who are in foster care,” Leondires says. “There are 100,000 waiting for permanent homes. But in the interest of religious freedom, they [the plaintiff and the previous administration were] allowing that discrimination at the peril of 100,000 children waiting for their forever home.”

Becoming A Family

Rosenberg assumed that he would never be a parent after he was diagnosed with HIV, the virus that causes AIDS, in 1990. He met van Gameren three years later. Although he recognized at some point that those who were HIV positive were living long lives with proper medication, diet, and exercise, the two were still torn about parenthood, but eventually they knew that the enjoyment they derived from parenting a dog and from spending time with their nieces and nephews pointed to one simple conclusion: they had to become dads.

Rosenberg says van Gameren, especially, “could see my love for kids and he knew that if I didn’t have kids, I’d really regret it.”

The couple’s formerly quiet home is now full – of noise, fun, and love.

“Our life is crazy and exhausting but it’s awesome. I wouldn’t change it for anything,” Rosenberg says. “I would imagine it’s no different for anyone else who has three kids and two dogs.”

More Stories

Small Caucus, Mighty Legislative Agenda

“It’s very scary and very exciting”: Jacques Lamarre on the World Premiere of Circus Fire and Building a Life in Hartford

How Can They Keep from Singing?