Author shines light on LGBTQ echoes in the characters, and life, of Thornton Wilder

By FRANK RIZZO

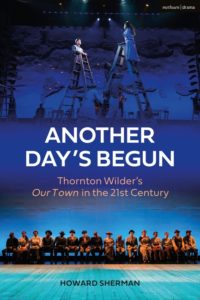

In Howard Sherman’s newly published book Another Day’s Begun – his “biography of a play” on Thornton Wilder’s Our Town – several actors interviewed talked about the LGBTQ subtexts they found in the classic work.

In Howard Sherman’s newly published book Another Day’s Begun – his “biography of a play” on Thornton Wilder’s Our Town – several actors interviewed talked about the LGBTQ subtexts they found in the classic work.

As reflected in the new book’s subtitle, “Thornton Wilder’s Our Town in the 21st Century,” Sherman deals with contemporary approaches to the metatheatrical work which had its Broadway premiere in 1938 and still remains one of the most-produced American plays. Sherman’s book includes interviews with more than 100 artists who have staged adaptations of the play or have otherwise been inspired by it.

Set at the turn of the last century in the small, fictional New Hampshire town of Grover’s Corners, and detailing the unremarkable minutiae of family and civic life there, Our Town is sometimes thought of as an old-fashioned, sentimental work of vintage Americana. Nothing could be further from the dozen wide-ranging productions that Sherman, a New Haven native, profiles in his book, all of which have taken place in the last 20 years.

Some of these productions served as a community balm following national and local tragedies. A 2002 production at the Westport Country Playhouse starring Paul Newman followed the shock of the 9/11 attacks. (That version transferred to Broadway and was later televised for PBS.) Another production in Manchester, England by the Royal Exchange Theatre followed the 2017 arena bombing there.

Sherman also profiles David Cromer’s New York landmark work in 2009-10 – the longest run of the play in its 83-year history – as well as productions as varied as those by Deaf West Theatre in Los Angeles, which incorporated American Sign Language, and the Miami New Drama production, which was trilingual.

Sherman also includes several extraordinary amateur productions, too, including one presented at a Pennsylvania mental health facility in 2014 and another at Sing Sing Correctional Facility in New York in 2013. “That was one of the most extraordinary theater experiences I’ve ever had,” says Sherman, who worked at Hartford Stage, Goodspeed Musicals and the Eugene O’Neill Theater Center in Connecticut, prior to a run as executive director of the American Theatre Wing.

The play – seemingly mundane, until it’s not – often affects both actors and audiences in profound ways, Sherman learned.

As one of the Sing Sing inmates said of the play: “It’s like a ‘Seinfeld’ episode. This is a play about nothing until it’s revealed that it’s everything. Your family, your friends, every moment of each day that you’re experiencing while you’re waiting for something to happen; everything is happening right now.”

Finding An LGBTQ Audience

“What I also found moving,” says Sherman, “was a production I saw entirely by trans-queer actors as part of the Pride plays last year. It was very interesting that in a program of otherwise ‘alt’ plays explicitly about the LGBTQ experience, their opening night play was Our Town.”

Wilder’s Grover’s Corners was originally presented as being an entirely white and seemingly entirely heterosexual community, says Sherman. “Yet the play can encompass a vast variety of experiences without ever needing to change a word of the text. That goes to gender, that goes to disability, that goes to race and ethnicity – and that’s part of why I think the play continues to live.”

LGBTQ audiences may also connect with the play’s character of Simon Stimson, the town’s choir master, whose alcoholism and undisclosed “troubles” have been the subject of gossip. Later in the play, we learn that the character commits suicide.

“It was a very different time,” says Sherman. “You can read into the Stimson character a great many things. There’s no question that he is a choir master who is obviously frustrated and unhappy. He could perhaps represent a closeted man, especially in the era of Grover’s Corners at the early part of the 20th century. Simon Stimson, certainly in his frustration, in his otherness, in that era is easily, and to my mind, perfectly and legitimately often interpreted as a closeted gay man at a time when such a thing would not be discussed yet. In a small community, [it was] probably known by many people but they just didn’t talk about it.”

One actor who played the character in a production Sherman profiles says: “The play, when it starts out, it’s like a Norman Rockwell painting and Stimson doesn’t fit in there.” Another actor in a separate production says he “chose to play him gay. It was very easy to find that in him…so I think he realizes that that’s what’s different about him.” Still another actor says: “I very much agree with the theory that he was gay at a time when he really wasn’t permitted to be openly, and I think that’s Thornton Wilder airing that side of himself, the side of himself that he felt he had to keep locked up.”

Wilder Times

It was a don’t ask/don’t tell dynamic with which Wilder, too, could identify.

Robert Gottlieb wrote in 2012 in “The New Yorker” of the omissions in “the biography,” Thornton Wilder: A Life by Penelope Niven, “She ignores (or doesn’t recognize) disturbing complexities in Wilder’s nature and slides past episodes and relationships that are less than attractive.”

“To his father, Thornton, though clearly brilliant, was also a weakling, a dilettante,” writes Gottlieb. “Every summer, well into his twenties, his father sent him off to do physical labor on farms, thereby ‘ridding him of his peculiar gait and certain effeminate ways.’”

Although Wilder never discussed being gay publicly or in his writings, Samuel Steward, an intimate friend – introduced by Wilder’s close confident, author Gertrude Stein – is acknowledged by some to have been a lover of Wilder. Steward chronicled in detail his relationship with Wilder in a book of his own.

A 1920 Yale University grad, Wilder purchased a home in Hamden later that decade where he, his mother, and his sister Isabel lived all their lives. Though Wilder was a regular at the Anchor bar in downtown New Haven, his time spent in the area was limited. He used the Hamden residence more as a home base, spending much of his life traveling abroad and throughout the United States. Wilder died in Hamden of heart failure in 1975 at the age of 78. Isabel died in 1995.

Wilder’s first book was 1926’s The Cabala but it wasn’t until his second novel the following year – The Bridge of San Luis Rey, which earned the first of his three Pulitzer Prizes – that his literary career was launched. Turning to playwriting in the late ’20s, he had a series of one-act works produced, but it wasn’t until Our Town that his reputation in theater was made, followed by another nonconforming masterwork, the Pulitzer-winning The Skin of Our Teeth.

Wilder began Our Town in 1936, writing it primarily at The MacDowell Colony in New Hampshire and then at an isolated hotel in Zürich, Switzerland. The third act of Our Town was allegedly drafted after a long walk, during his brief affair with Steward in Zürich.

Many versions of the play followed, including the 1940 film that starred William Holden as George and – spoiler alert – created a happy ending. (Emily lives! Her death was just a bad dream.) There was also a musical version for television in 1955, with Frank Sinatra as the stage manager and Paul Newman as George (and which featured the now-standard tune, “Love and Marriage”). After Wilder’s death, there was a Ned Rorem opera in 2006 and in the late ’80s, a stage musical version of the play planned to tour but was cancelled in 1989 when its star, Mary Martin, bowed out because of illness.

Cry For Us All

The power of the play is revealed through the hard-edged existentialism and relatable philosophy that comes in the third act, set in a cemetery and the great beyond. The storyline leaps from the joyous marriage of George and Emily at the end of the second act to the audience suddenly discovering that the play’s young heroine has died in childbirth and has joined other deceased community members in the town cemetery. She implores the omnipotent character of the Stage Manager to allow her to return invisibly for one more glimpse of her past life. But while she now sees all the small wonders of life, she also realizes they are not appreciated by those living in their everyday existence.

Playwright John Guare called the third act of the play a “coup de theatre that helps sweep the play out of the commonplace into the realm of the eternal.” Playwright Edward Albee called the play “brutal,” adding, “You should be crying at the end of Our Town, not for the characters but for ourselves.”

Sherman says he wouldn’t be surprised to see a surge of productions of Our Town – and its embrace of mindfulness – once the current pandemic reaches the point when theaters are allowed to reopen. He says a theater in Australia has already announced that Our Town will be the first play it presents when it reopens.

“It does feel like we were all spending 2020 in Act Three. Thanks to science, there will be an Act Four for us. We aren’t Emily. We will go back and hopefully we will take from this the best lessons – that we appreciate the things we have that we could not experience during the pandemic, and then keep them to the best of our ability.”

More Stories

Off Broadway Review: Data

Broadway Review: Bug

Off Broadway Feature: Audrey Heffernan Meyer in “Art of Leaving”