Where’s Mommy?

Paula Vogel’s new play is disappointing and shallow.

BY CHRISTOPHER BYRNE

Virtually anyone who has been to the theater in the past 40 years will recognize that when a play begins and it’s clear that it’s a memory…and one of the main characters pulls a stuffed animal out of a box…and hugs it…and says, “When my brother Carl died…” you know it’s going to be a play about AIDS. This, and similar, tropes have in the past four decades gone from being emotional triggers to tired, manipulative, dramatic shorthand.

One can’t quite criticize playwright Paula Vogel of appropriating AIDS as a plot device, since her new work The Mother Play is based on her own lived experience with her brother Carl who died of complications of the syndrome in 1988. One can, however, point out the appropriation of Tennessee Williams. The Mother Play, depending on your point of view, is either an homage to, or blatant rip off of, William’s The Glass Menagerie, one of the all-time American classics.

I’m decidedly in the latter camp. I left the theater dubbing the play “The Plexiglas Menagerie.” On the surface it might be shiny, but it is a cheap imitation and by its nature can never refract light as real crystal does. Vogel’s play has neither the emotional heft nor the lyricism of Williams. Whereas Williams concentrates the action into one summer in sultry St. Louis, Vogel’s play is episodic, spanning nearly 60 years. As a result, the scenes are hasty sketches, leaving the audience—should they feel so inclined—to fill in the emotional blanks.

Nor does Mother Play have the cultural context Williams had. In The Glass Menagerie, Tom the narrator, looks back at his dysfunctional family, but his tragedy is that as a member of The Lost Generation—the cohort of young men following World War I—he is torn between taking care of his family, including his awful mother, and pursuing his own dream. That tension suffuses the action of William’s play. Vogel’s work on the other hand is scattered and fragmented.

For example Vogel gives her narrator character Martha no real depth and no internal conflict for an audience to relate to as the tale unfolds. Vogel seems to think that it’s enough to make her long-suffering in a sea of dysfunction. It is not.

Phyllis, the titular mother, is a struggling divorcee with alcoholic tendencies who dotes on her son and tolerates her daughter. As with Williams’ Amanda Wingfield, Phyllis is fearful for her daughter’s future, alone and unmarried with no man to support her. (This gets ever more implausible as the century progresses.) It’s clear brother Carl is gay from the outset, although that’s delivered in all manner of overworked clichés that indicate “gay,” but Phyllis can’t see it, apparently. When she does, she disowns Carl, at least emotionally, since scant finances are a recurring theme in this family. The scenes progress from grade school to high school to college and adulthood. Martha comes out, too. Phyllis declines and suffers from dementia, and Martha becomes the caretaker, compromising her own life. It’s unclear if Martha finally accepts that her mother is, for all intents and purposes, gone and that relationship will never resolve in a healthy way, or whether for Martha she’s ultimately resigned to more suffering or free? More importantly, at this point, why should an audience care? We never really understand the damage Phyllis has inflicted on Martha or its costs. This may be cathartic for anyone who has dealt with a parent with dementia to see this on the stage, but that’s not theater; it’s therapy.

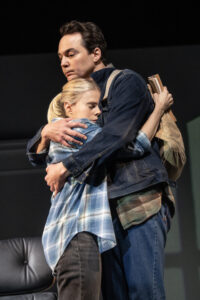

Director Tina Landau does what she can with the thin material, but the episodic structure never allows a scene or character to develop. The usually stellar cast struggles with the material as well. Neither Celia Keenan-Bolger as Martha nor Jim Parsons as Carl can manage playing children without cringe-inducing awkwardness.

Keenan-Bolger, who was a profound and complex Laura in the 2013 Broadway revival of the Glass Menagerie, simply hasn’t been given enough to work with. The play doesn’t capitalize on her incredible talent until the last scene with her mother, where she’s given the time to express some more complex emotions. We knew Keenan-Bolger had that in her…Martha not so much.

Jim Parsons, another brilliant actor, as Carl is reduced by the shallow part to indicating emotions and moments. It’s not his fault. In leaning heavily on exposition, Vogel seems almost afraid to explore Carl’s inner life, so his homosexuality and the tragedy of AIDS is facile and trivialized—almost a gimmick. It doesn’t help that he appears near the end with Kaposi’s Sarcoma lesions on his face that look like stuck-on Colorforms.

Jessica Lange, who played Amanda in Menagerie on Broadway nearly twenty years ago is, as always, in command of the stage, but the writing limits her. The tragedy of Amanda is that she is lost in her own narcissism and another time and that she refuses to see the impossibility of recapturing a vanished world or that her daughter is crippled physically and emotionally. Phyllis, in Vogel’s play, has no such life to work with, so she’s merely angry and resentful. Moreover, Landau has given Lange an extended silent scene in one of the apartments the family has to live in. One supposes it’s to provide insight into what makes Phyllis tick, but it comes off as tedious, extended “private moments” exercise—the type of thing popular in beginning acting classes.

Memory is fallible, and autobiography is often untrustworthy. That can make great theater, but not always. In the case of The Mother Play, the best we can hope is that Vogel has exorcised some of her demons and can go back to writing the incredible plays, such as Indecent, that have been the majority of her work.

Mother Play

Second Stage at the Hayes Theater

240 West 44th Street, Manhattan

Tues-Sat 7 p.m.; Weds, Sat 2 p.m.; Sun 3 p.m.

Tickets from $159 here.

1 hour, 45 mins, no intermission

Production photos by Joan Marcus

Published May 5, 2024

More Stories

Off-Broadway Review: Trophy Boys

Broadway Preview: Lewis Flinn’s Cabaret

Off-Broadway Revew: The Imaginary Invalid