If the future is truly genderless, as one might hope, it begs the question–what will this genderless future look like? What interpersonal barriers will gender fluidity remove, and how will these shifts be expressed in our daily lives?

Themes of intimacy, gender, and domesticity animate the artwork of Paul DeRuvo, a nonbinary fine artist and collaborative printmaker. A Connecticut native, DeRuvo works as a collaborative printmaker and a studio manager at Norwalk’s Center for Contemporary Printmaking. They’ve exhibited in New York City, Boston, San Francisco, and Berlin, where they held a solo show, Love and Isolation. Utilizing the craft of fine painting and the devotional act of representational drawing, DeRuvo seeks to depict the impact gender fluidity has on interior spaces, as well as to highlight the resonance it carries universally.

We spoke with DeRuvo about their practice and their insistence that “the personal is political.” DeRuvo’s work with the CCP culminates in an auction event this Saturday at New Canaan’s Carriage Barn Arts Center–join them for an evening of fun, food, and fabulous art!

CT VOICE: You are a Connecticut native, and you first began classes at the Center for Contemporary Printmaking in high school. What are the benefits and challenges to maintaining an artistic practice in Connecticut? What influence does Connecticut have on your work and your process?

PAUL DERUVO: I started working at the CCP when I was fourteen, and at the time, there was no program for high school students. I told them I wanted to start coming, and they could put me to work—they could give me a broom, something like that. They allowed me to intern for them despite there not being a program for students.

In Connecticut, we have a rich history of historical buildings, and it’s really pretty amazing. The city of Norwalk has given the CCP the chance to exist through its space, which is part of the Lockwood-Mathews Mansion. My practice has been most heavily influenced by the existence of these buildings, and the creative repurposing of them on the state and city level. The CCP has been able to exist, which is why I chose to return to Connecticut. Without the CCP, I probably wouldn’t have found myself back here. If you don’t have a space, there is nowhere to create work—and this is the challenge that many young artists face currently.

CT VOICE: Your work deals primarily with themes of love, intimacy, and gender. How much of your own experience as a queer, nonbinary person informs and inspires your practice? Where else do you seek inspiration for your practice?

PAUL DERUVO: My work is fully influenced by my experience as a queer person, but I look for elements of my experience that can be both universal and especially significant to queer and trans people. A lot of my work explores ritual and identity creation, and the more I’ve thought about these ideas, the more I’ve learned that everybody has experienced them. I’m looking for a way to make these themes resonate with everybody on a human level.

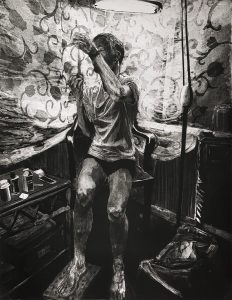

One of my pieces, “Shot Day,” is a piece in which I portray my experience of a partner taking his testosterone shot. It’s a piece I’ve avoided making for a long time, because I was worried about the clichés surrounding the over-fixation on trans people’s experiences with medical care and the focus on conversations around artifice that often follow. In making the piece, however, I decided that this was a moment that allows other viewers to go on a journey, and potentially connect with something either deeply familiar, or possibly strange — the act of self-administering an injection. Where depending on the viewer it might echo the opioid crisis or other private experiences, the more you pick it apart the specific narrative emerges: the pharmacy issued box, the alcohol swab, the pose. Whether you are someone of trans experience or not, these moments have the potential to resonate and connect to scenes which rarely have the chance to be shared with amount of care and nuance they deserve, and if you share that experience then it is a chance to see that moment reflected.

CT VOICE: Do you feel your work carries social/political reverberations, or do you prefer to view it within a vacuum? Do you feel there is an added pressure for queer/trans artists to politicize or instrumentalize their art?

PAUL DERUVO: I’ve always found a lot of inspiration in the notion that the personal is political. I make work that is wholly personal, and I trust that there is always a political element to it. At the end of the day, the relationships we build and the ways in which we share honest views of our lives is the only thing that gives people an opportunity to broaden and give nuance to their own experience. As a queer and nonbinary person, my art gives me whole new frames in which to view my relationship to my body and to my partnerships, which has been life-changing and life-saving. Without an alternate framework, we have only the most rigid narratives. And the lack of possibility really diminishes people’s lives when they can’t imagine different modes.

CT VOICE: On the subject of the personal as political, it’s interesting you say that. So much of queer arts movements in America has been focused on the idea of radical disclosure, of finding forms to yield these insights.

PAUL DERUVO: Around radical disclosure, it’s important to think about which disclosures are truly radical, and how do we avoid exploiting experience? How can we be sensitive and how can we avoid sensationalism? We can increasingly see that there is a disconnect for queer and trans people who feel we can be open in certain spaces, like on the Internet, but we can’t move through the world in the same way. So in my work, I want to reimagine what it would be like for us to go through our daily lives with complete openness.

CT VOICE: With the rise of the Internet, the “creative class,” and an economy that is increasingly focused on the visual, it is understandable that many young artists might feel more compelled to enter commercial art. For you, what advantages remain in pursuing a fine arts practice? Do you see any added imperative for queer people to pursue fine arts?

PAUL DERUVO: For me, fine art allows me to reclaim the representations of queer people, which is too often dictated by elite institutions. In commercial art, you don’t get to decide your own narrative, whereas fine art requires you to be specific to your own experience. It wasn’t always that identity and narrative were conversations in the art world. I’m sure there are still artists who assert that their work is not influenced by their identity, and that may be true, but that hasn’t been my experience. Fine art has been a place where I can speak to my own experience without sacrificing it in the service of a brand or narrative.

As far as queer artists making a living—I was just on a panel giving a talk on careers in printmaking, and I tried to remind people of all the skills we learn in becoming an artist. The ability to document your work, to describe it, the writing skills of making your own artist statement. These skills require practice, but they are actually very professionalizing and marketable. They’re not secondary; just the problem-solving of having an arts practice is extremely valuable to organizations. More people should hire artists, because we know how to adapt and seek solutions!

CT VOICE: In addition to your practice, you work at the CCP as a studio manager. For you, how important is it to have queer representation in arts administration?

PAUL DERUVO: Having individuals within the organization who continuously advocate for queer representation is one of the most important things. We have school groups in at the CCP, and for them to see queer people in the professional workplace shows young people that you can be valuable and supported no matter who you are. Being present as a queer person in administration, you show that you’re welcome, you can advocate for other queer people, you show that other queer people can participate. And as language changes around identity and pronoun usage, you can serve as a liaison between older and younger generations.

More Stories

Make It Here, Just As You Are

Queer Joy and Queer Resilience

The Final Word: Embracing Differences