When gay culture winkingly slipped into the mainstream

Written & Photographed By FRANK RIZZO

Billy Ordynowicz and Lawrence Degley have a gay obsession.

Over the past few years Ordynowicz, a 38-year-old theater technician and Degley, a 43-year-old claims adjuster, have developed a fascination for vintage gay-related periodicals, especially those of the second half of the 20th Century.

“We can’t forget what our community had to go through to get to where we are now,” says Ordynowicz, who compares their ephemera pursuit to modern hipsters collecting vinyl records to better appreciate and honor a past culture.

There was an air of danger, he says, for gay men and women during that subterranean era when deep secrets, knowing glances, and coded words were de rigueur in order to keep jobs, families, and reputations intact while still being able to connect with other LBGTQ persons.

There was an air of danger, he says, for gay men and women during that subterranean era when deep secrets, knowing glances, and coded words were de rigueur in order to keep jobs, families, and reputations intact while still being able to connect with other LBGTQ persons.

Degley and Ordynowicz, who live in West Haven, are especially intrigued with After Dark magazine, published from 1968 to 1983.

“After Dark was as closeted as the gays had to be then,” says Degley. “Still, if you were a closeted gay man, you just knew the magazine was for you. But for others, it usually went right over their heads.”

Secret Selves

Degley’s and Ordynowicz’s passion for the publication brought to mind my own love of the glossy magazine. I remember spending 50 cents and picking up its first issue in May 1968 at a Boston newsstand. It was as if I just shook hands with my secret self.

That magazine and the 168 that followed (all of which I‘ve treasured like old friends) reflected all the things I love: theater; dance; television; cabaret; visual arts; film; fashion; opera; pop music; and beautiful, sexy men. It was a champion of experimental art, cutting-edge theater, and up-and-coming artists. It embraced sensuality on any kind of stage, be it Vegas clubs, circus tents, ice rinks, or bullrings.

“It was a lifestyle and celebrity magazine as seen through a gay male lens,” says New York-based Eric Marcus, creator of the podcast Gay History. “It was clearly a gay magazine, but it could pretend that it wasn’t.”

Yes, there were plenty photographs of handsome shirtless men; gay icons like Liza, Bette, and Rudi; sexy spreads of Andy Warhol; stars and glamour gals from an earlier era like Mae West, Ginger Rogers, and Veronica Lake – but there were also stories about hetero cover boys such as Burt Reynolds, Robert Redford, Mikhail Baryshnikov, and Arnold Schwarzenegger, too.

As for the ads in the back of the magazine for mail-order fashions by Ah Men, Parr of Arizona, and International Male – and curious places like the Club Baths – one could always plead the Playboy magazine defense, “Oh, I just buy the magazine for the stories.”

But After Dark wasn’t beloved by the entire LGBTQ community. Says Patrick Pacheco, a former writer and editor of the magazine: “Gay activists had some disdain for the magazine and its closeted staff and its lack of political action and activity. They saw us as dilettantes.”

That was understandable, given the content of divas, disco and hunks. But as lightweight and dishy as it was, in its own way it was subversive.

Marcus points to the magazine’s ability to connect the gay community on a national level with a shared cultural aesthetic. “It served an important role of being visible,” he says.

For those in communities that weren’t on the front lines of the gay rights movement, After Dark still made you feel part of something larger than yourself, especially in closeted times. “I would be more comfortable picking up a copy of After Dark,” says Marcus, “than I would be picking up a copy of The Advocate.”

The Changing Times

The launch of the magazine emerged from the ‘60s decade of sexual revolution, artistic experimentation, and a massive generational shift in society, politics, and culture. And it celebrated such liberating signifiers as “Hair,” “Barbarella,” “Oh! Calcutta!,” “The Rocky Horror Picture Show,” drag, and disco.

“The post-Stonewall days was a period of enormous flowering of gay male sexuality and of gay and lesbian liberation, and that’s what you saw in the pages of After Dark,” says Marcus “It was an ‘opening up’ that hadn’t been experienced before.”

Marcus notes, however, that the magazine was aimed at a particular demographic that advertisers were just starting to be interested in. “After Dark offered one perspective on gay male life, certainly that of young, middle- and upper-class gay men, and served that very specific market.”

It was one that journalist Patrick Pacheco knew well. Pacheco started at the magazine in 1972 as a gofer, then worked his way up as writer, managing editor and, in its final year, editor-in-chief.

He first discovered After Dark in the early ‘70s. “I was in college, after having left the Catholic seminary, and a friend in the Hollywood Hills had a copy on his coffee table,” says Pacheco. “It seemed like the most exciting magazine in the world. I was struck by its view of New York, its chic and urban sophistication, its inclusion of world cinema – and all of that erotic content – and, of course, the nude pictures. These photographs would often have a woman in there with the naked man, but there was no question that male beauty was at the forefront.”

Cover Boys and Girls

The visionaries of the magazine were its founding editor-in-chief, William Como, and its managing editor, Craig Zadan; the latter would go on to be a major film and television producer. After Dark’s visual style was also shaped by its art director, Neil Appelbaum, and especially its principal photographer, Kenn Duncan.

“Kenn could not only convey a certain eroticism in his work but also a kind of innocence,” says Pacheco. “There might be a hunky, shirtless male model or actor being photographed but instead of a giving a come-hither look, he would be laughing. Playful eroticism was key.”

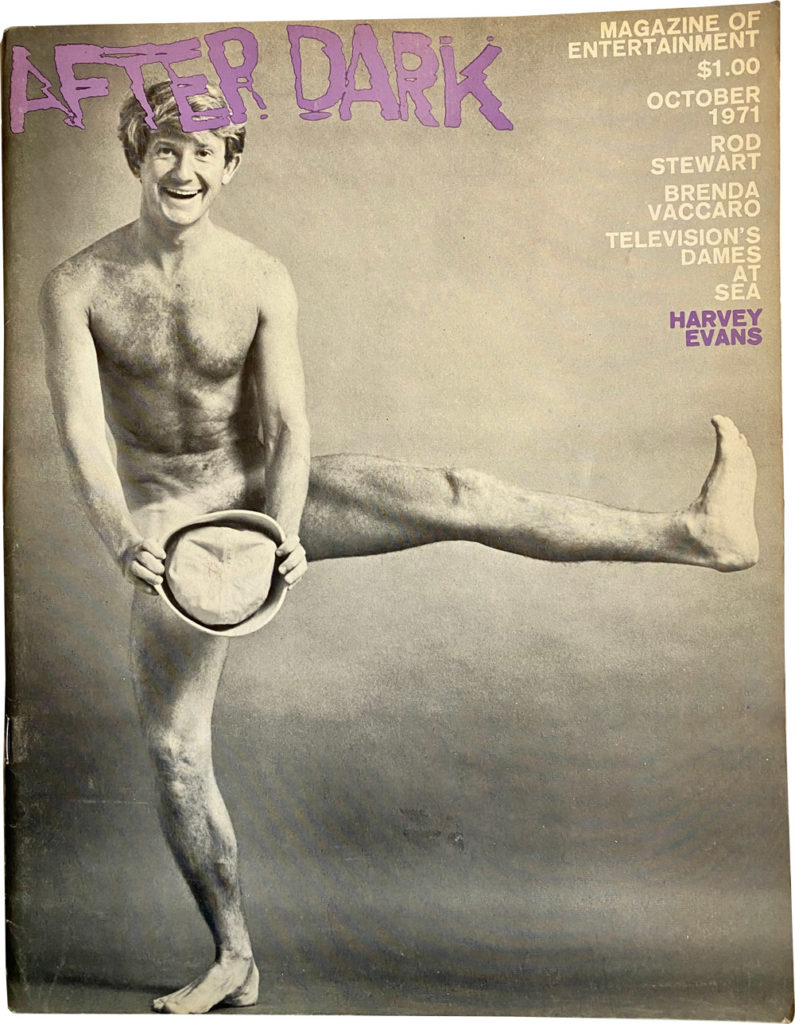

Harvey Evans was in the original Broadway production of “Follies” in 1971 – and was about to be featured in the television version of the musical “Dames at Sea” – when he was invited to be in a photo shoot for the magazine.

“I told my friends that I would be photographed by Kenn Duncan and that I would definitely not take my clothes off. But when I got there, Kenn was so charming and delightfully funny, within a half hour I had my clothes off,” recalls Evans, now 80. “Of course, I loved the magazine. Where else could you read about Maureen Stapleton on one page and see a naked person on the next? Some liked the showbiz element and some liked the sexiness of it.”

It turned out that the main photograph of the shoot would be the magazine’s cover in October 1971, and one of the magazine’s most memorable, featuring a naked Evans playfully dancing, holding his sailor cap strategically in front of him.

When the issue came out, Evans sent a copy of the magazine to his father, “who remarked, ‘Your body’s not bad.’ I was an out gay man but we didn’t talk about that.”

Another iconic cover capturing that sense of joyous abandon was of Rory Foster, who was a dancer with the American Ballet Theatre in the ‘70s.

“Everyone loved After Dark,” says Foster, “Broadway people, dancers, artists. It was kind of cutting-edge at the time because of the stuff that Bill put in – those risqué, semi-nude photos that made some people blush but, overall, people were really excited by this. They were really hungry for what’s happening in all the arts.”

On the December 1971 issue cover, Foster wore short-shorts and an open shirt, dripping wet from being sprayed with a hose and looking rapturous with outstretched, welcoming arms.

“My roommate at the time kind of summed it up. He held up the cover and said, ‘The face that launched a thousand orgasms.’”

For June Gable, who earned a Tony Award nomination for the 1974 Harold Prince revival of “Candide,” After Dark meant a mixed bag of feelings for a lot of her friends. “Some thought it was almost pornographic,” says Gable, who was on a spoofy cover in December 1978. “Others just loved it. I thought it was fabulous. It was bold, joyous, and free. It celebrated bodies, a new culture, and it opened up doors for a lot of people.”

Actor Keir Dullea doesn’t remember much of his photo shoot. At the time, his career was red-hot after starring in “2001: A Space Odyssey” and Broadway’s “Butterflies Are Free.” For his September 1970 cover, he was paired with Susan Browning, who was starring in the musical “Company.”

“It wasn’t a magazine I had been familiar with,” says Dullea from his Connecticut home, “but I was happy to do the publicity.”

He doesn’t remember much of the shoot – or the magazine. But what stayed in his mind was the over-the-top ‘70s clothes he was given to wear; think double knit jumpsuits and see-through voile shirts. “Let’s just say they were clothes I would not wear for myself,” he says laughing.

A Bette, A Penis, And The End

“No question that After Dark’s cachet in the entertainment world came from its early discovery of Bette Midler,” says Pacheco, of the star who began her career singing at The Continental Baths before an audience of gay men wearing towels.

“Record companies in particular would look at After Dark, especially during the disco period, and we did cover stories on Donna Summer, Helen Schneider, Ellen Greene. We were constantly being bombarded by publicists who wanted to break through with their up-and-coming performers.”

Male stars were a different matter. “If they cooperated, people might think they were gay,” says Pacheco. One of the major exceptions was Schwarzenegger, who was on the February 1977. cover. >>

The beefcake cover and what was inside made it the biggest-selling issue.

“Arnold had no problem with appearing in the magazine because he was secure in his heterosexuality and he was just breaking through films at the time,” says Pacheco, who wrote the cover story. However, Schwarzenegger was not pleased when an inside picture showed him naked in a locker room with his penis peeking out from a towel. Pacheco reminded him that he approved all the pictures used and besides, it was so small – the picture, that is – no one would notice.

The magazine began a slow decline in the late ’70s. Como left in 1980 to work solely at Dance Magazine, having become editor-in-chief at that publication in 1969. Subsequent editors of After Dark realized that the magazine’s tasteful eroticism couldn’t compete with the explicit male nudity in new, plastic-wrapped periodicals like Blueboy, Mandate, and Playgirl. A new strategy of diminishing After Dark’s gay identity and moving more mainstream didn’t work either, when it found it couldn’t compete with big-time celebrity magazines like People and Us that took over newsstands in the mid and late ‘70s.

After Dark bookended two LGBTQ landmarks and was a chronicler of that special time of liberation and innocence. The magazine that began just before Stonewall published its final issue in January 1983 – one month before The New York Times Magazine reported on the birth of a new disease called AIDS.

“We thought it would go on forever,” says Pacheco, “but the party was over.”

More Stories

Fall Arts Preview: Emus, Foxes and Eric Clapton, Too

Diane DiMassa Book Event September 25

Off-Broadway Review: Trophy Boys