At Middlesex Health, transgender patients find empathy and assistance

By James Battaglio

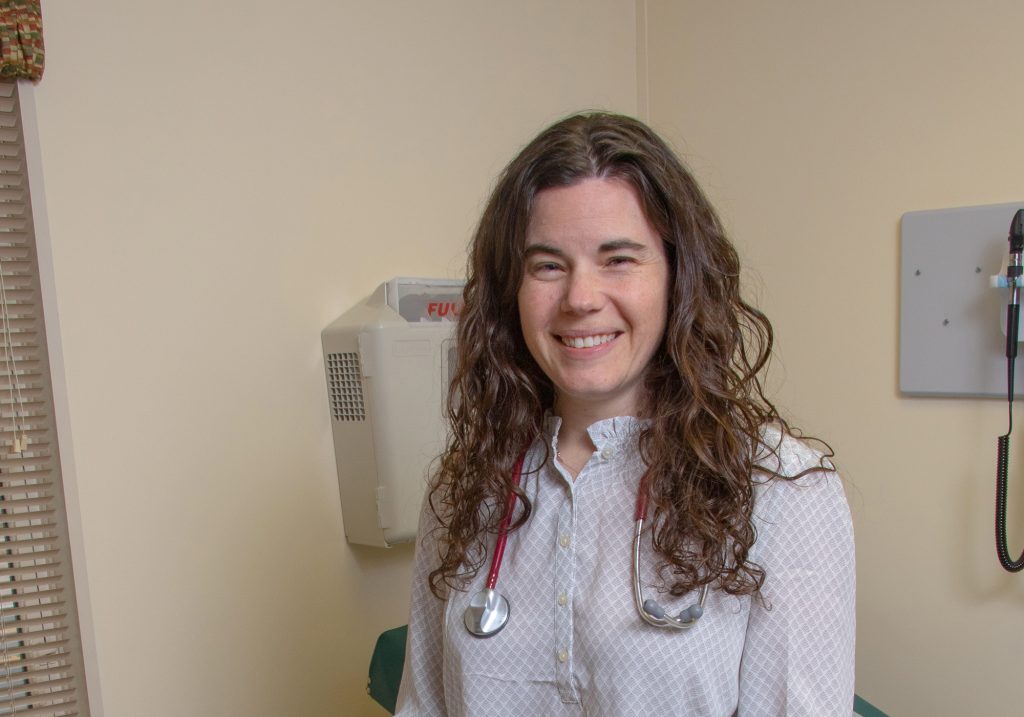

Those considering hosting a gender reveal party may wish to hold off a few years before announcing the gender of their child. Such parties, which are becoming a popular trend among expectant parents while their child is still in utero, are premature, according to Kathryn Tierney, MSN APRN, FNP-BC, medical director of Middlesex Health’s Transgender Medicine Program.

“Gender reveal parties are not actually correct,” says Tierney. “You may see a cake that’s pink in the middle or people releasing certain color balloons that represent the gender of their expectant baby. The problem is that the word ‘gender’ doesn’t actually mean what kind of genitals a baby has. You don’t know what gender that baby is because our gender is defined by our culture – and the baby or child needs to experience our culture before their gender identity is known.”

Tierney says her patients consistently tell her that at a very early age, they knew their gender differed from their birth sex. “When I ask our transgender patients how they knew they were a certain gender, they tell me that when they were young kids, they knew something was different about them, that something wasn’t right. Mothers would tell girls to wear a dress and the child felt that was crazy. Or a father wanted his son to play baseball and the child would feel that it didn’t fit with his internal sense of identity,” she explains.

Tierney, a Cheshire resident and mother of two, came to Middlesex Health from the Hospital of Central Connecticut in 2014. Since 2006, the nurse practitioner has specialized in transgender hormone therapy and endocrinology. “Transgender care encompasses all types of care, but in endocrinology, we take care of the hormonal part of it,” she says. Middlesex Health treats some 700 patients a year, starting or continuing hormones for patients who are transitioning from one gender to the other “or finding their way in the middle.”

New transgender patients who are being treated with hormone therapy are evaluated at least every three months for the first year, and every six to 12 months after that. These patients are seen sooner if acute issues occur. Tierney explains that for transgender patients, there is a “disconnect” between the body they’re born with and their real identity.

“This is where the rub is,” she says. “For almost all of us, our gender identity matches the kind of body we were born into. For transgender people, most of them are born into a body that doesn’t match.”

For the most part, gender identity is solidified between ages 2 and 4, says Tierney. That’s when most kids start dividing into groups when playing. A lot of her patients will tell her they were born male and were expected to do male things, but they would prefer to be with their mother or with female friends, or do things that society would consider female.

“It gets harder to understand it because we’re pushing into a world where girls can play baseball and boys can do art, but in our culture, we have very set things that are male and female, and boys and girls are expected to do a certain number of things that make them fit into their gender. When the way we see our self internally doesn’t match with the way the world sees us, it makes it very uncomfortable for these patients,” she says.

“The expectations of these children, starting early, were that they were to act a certain way. When they didn’t, that’s when they realized they were different.” Years ago, young males with effeminate traits or preferences were termed “sissies,” while young females with some masculine traits or preferences were known as tomboys. Both terms have pretty much worked their way out of today’s social lexicon, Tierney says.

She says “the word ‘transition’ encompasses a lot of things for people who are transitioning from one gender to another.” Not all female patients who are transitioning to male – or male patients transitioning to female – undergo surgery, says Tierney, because the transition from one gender to another has less to do with one’s physical body and more to do with one’s identity. Still, she notes, “our physical presentation is important in our culture.”

Trans men generally receive testosterone injections, which results in beard growth and a deeper voice. These patients present as male but still have a female chest. “That makes it much more difficult for them to be themselves in public,” says Tierney. “So they have chest surgery to flatten their chests to the degree that a male has. What they choose to do with their genitals is completely a personal decision; there’s no such thing as a ‘complete’ transition. Everybody has to transition in the way they’re comfortable in their body. Sometimes that means hormones and surgery, and sometimes that means surgery only. It depends on the person.”

For the trans male patients who choose surgery, there are a number of options. “Chest surgery is the most common and most dysphoria-reducing surgery that trans men undergo,” Tierney says. Chest surgery, or “top surgery,” as it is widely referred to, is a double mastectomy in which breast tissue is removed and the chest is contoured to give it a male appearance. This surgery may include nipple grafts, or nipple/areola resizing and repositioning. Afterwards, patients no longer have to wear binders to flatten their chests.

This makes them a lot more comfortable, both physically and psychologically. Some of these patients opt for genital surgery as well. In metoidioplasty, existing genital tissue is used to form a neophallus, or new penis. (It can be performed on those with significant clitoral growth from the use of testosterone.) These patients can urinate but are not always able to engage in intercourse. Phalloplasty is a gender reassignment surgical procedure that involves grafting skin from an arm to create a penis with erotic and/or tactile sensation, as well as rigidity for sexual intercourse (usually with a penile implant) and the ability to stand to urinate. In both procedures, there are risks, says Tierney.

“Surgery is a personal choice for a variety of reasons, ranging from non-insurance, time away from work, or other co-morbidities that prevent them from safely having surgery,” says Tierney. “Some choose not to have any kind of surgery but to just remain on hormones. A lot of Connecticut residents have had surgery. The Connecticut TransAdvocacy Coalition worked hard to make sure that Connecticut residents have the option of having surgery through their insurance, and because of the coalition’s efforts, coverage of trans-related services is mandated in this state.”

For the trans female patient who chooses to undergo surgery, there are several procedures available. They include a tracheal shave to reduce the size of the Adam’s apple, voice therapy, breast augmentation, vaginoplasty, and testicle removal, Tierney says.

Of Middlesex Health’s 700 transgender patients, about 30% have had surgical procedures. When Tierney came to Middlesex in 2014, the health system began its commitment to introduce a comprehensive transgender program, which included the training of staff, volunteers, and “all the way up to our CEO,” she says.

Gender-neutral, single-stall lavatories for patients and the public were created so no one has to choose which bathroom to use. All employees (more than 3,100) and the 381-member active medical staff have undergone transgender training for which Middlesex has been nationally recognized. The institution has also been identified as a leader in healthcare equality several years in a row by the Human Rights Campaign’s Healthcare Equality Index.

Tierney, who grew up in a non-traditional family, recognized from a young age the cruelty often aimed at someone dubbed “queer.” Today, she heads a 30-member committee that meets monthly to review policies and ensure they’re in line with protecting transgender, gay and lesbian patients and employees.

“Ideally, the entire health system is involved in the transgender program,” she says. The committee includes Middlesex Health’s chief of psychiatry, who co-chairs the committee with Tierney; social workers; physical and speech therapists; nurses; Emergency Department professionals; and the chair of the Department of Medicine. “It’s my job to assure that providers are trained and educated in trans care, so that if a transgender patient shows up in the Emergency Department, I’m not the only one that knows how to take care of them correctly. ER personnel, radiology, specialists, surgeons, registrars … anybody coming in contact with a transgender patient should know how to address and treat a trans patient,” she explains. “It’s important to use the right name and right gender pronouns and make sure our charts and systems are presenting the patient as they are, and not as they were. Also, we make sure that, clinically, we’re being safe in which labs we’re looking at and which medications we’re using. You always want to make sure you’re not giving patients undue side effects.”

For Tierney, treating the transgender patient is more than just a profession. It’s a privilege, a cause and a vital service she performs daily. She’s quick to recognize that ransgender patients, in general, face a lot of discrimination in many ways, in employment, sexual assault, housing, and medical care, which is one of the reasons Middlesex works so diligently to ensure it doesn’t happen within their facility.

“If you’ve ever had an outfit that didn’t quite fit right, multiply that by 100 and live that every day,” she says. “The most rewarding part of my work is seeing people get their confidence and really being comfortable in their skin.”

For more information, visit

More Stories

Young, Queer Love: How Different Is It?

A Leader in Care for LGBTQ+ Communities: Meet Kenneth Abriola, MD

Transforming Sexuality: Handling Sexual Changes for Trans Folks