By JANE LATUS

Before Helene hit on September 27, Asheville was considered a climate haven. People moved there because of it. Of all things, hurricanes weren’t a worry there, 300 miles inland and 2,000 feet above sea level.

I’d been in Asheville since September 12, when I flew in to help my son Elliott with a medical emergency. The first few days were frenetic with MRIs and blood tests, and the fiasco that is the medical system there. It took 48 hours to get a critical prescription, thanks partly to the lack of a 24-hour pharmacy—unless you drive 3 hours roundtrip to the closest one in Tennessee.

Two weeks later, I couldn’t have driven to Tennessee if I tried. The roads were gone. And the kind pharmacist I’d spent several hours with my first Sunday in town, waiting for the doctor to phone in the right prescription to the right, and only open, drugstore, was dead.

You’d expect a disaster to be disastrous. But until you’re in one, you won’t get just how bad, and in what ways.

Most surprisingly harrowing were the sounds. The actual storm was the least of it. Worse were the constant drone of helicopters, circling low all day for weeks, searching for survivors and bodies. There were emergency sirens and fire alarms, nonstop night and day for over a month—and no airplanes since the airport was closed.

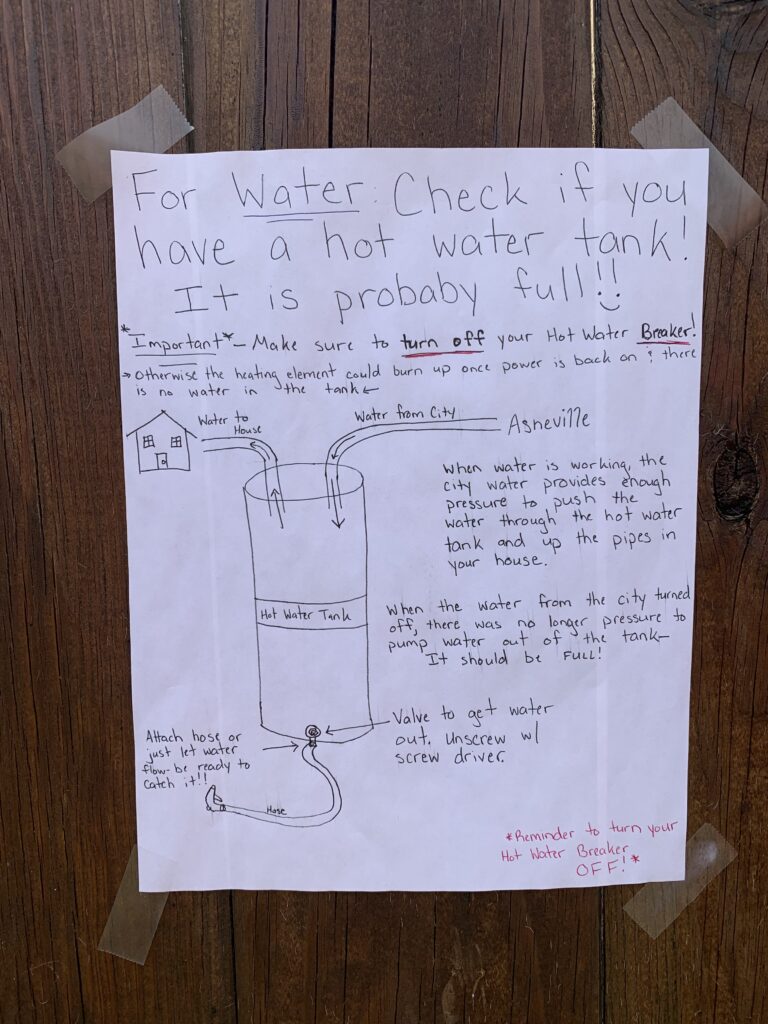

Water ruled our days. It had swept away the pharmacist, who was found 13 days later, miles downstream and killed more than 100 others locally by drowning, burial by mudslide, or lack of essential care like oxygen machines and insulin refrigeration. The water destroyed the homes and businesses of thousands, including many of my son’s friends and devastated the infrastructure. Water came home in my backpack, on foot, until power returned, a gas station opened, and I dared spare the gas to drive.

Some images will never fade. I’d expected overturned vehicles, but not cars in trees. Harder to forget are the trailers of FEMA rescue boats driving past me, the stunned looks on people’s faces and the faces of the dead in the news, as well as the weary bearing of the firefighters who told me of their previous 48 hours rescuing people from cars and trees, and how they couldn’t save them all.

The initial relief that only our basement was flooded was short lived.

The most terrifying period was the first few days, when we gradually learned of the extent and horror of the devastation, and of our complete isolation.

When the storm passed, I walked to the fire and police station, along with others eager for news. The last contact we’d had before cell service went out was from Elliott’s friend Alex, who texted that a tree was in his bedroom. News, it turned out, would for a couple of weeks come in the form of notices posted on the fence outside the station. The first news was shockingly bad: there was no way in or out of the county, by any means. Cell service and internet were out over a huge territory.

Cell service was out for three days, until I was able to tell my wife that yes, we were okay.

The isolation was worse for Elliott, stuck in bed, with the letters “SOS” on his phone where bars should be.

I was thankful to be fit, especially with Elliott out of commission physically. I was able to squat-walk across the flooded basement on upside-down-buckets to turn off the circuit breaker. I could hold heavy buckets high to flush. I could carry essentials home.

Every day, I’d tell Elliott, we’re a day closer to getting power and water back.

I can’t say I held it together. Only adrenaline and lack of time to think kept me going. A week post-storm, Elliott wasn’t any better. There was no indication of when help might arrive, or even when a guess could be made about when service restoration could begin.

That was the worst day, because things started to turn around. Local professionals started offering free services, usually outside because they didn’t have power or even a building. Elliott took up the offer of free acupuncture, and it immediately helped.

That night, a week after Helene, the power came on. Two hopeful signs in this double disaster. It would be another couple of weeks before federal aid reached us, but meanwhile, things got better because people helped each other.

Community is the only reason anyone made it.

If you anticipate a disaster, besides stockpiling the usual stuff, do what I neglected: take out lots of cash. Without power or internet, it’s all businesses can accept.

Unless you’re lucky enough to be in Asheville, where the West Village Market let people shop, in the darkness by phone flashlight, with credit card IOUs. I ate thawed frozen pizzas from there for two days.

Asheville has a lot of community spirit anyway, with a large LGBTQ+ population, lots of musicians and artists, and tons of local events and action. There were active mutual aid groups before the storm. People simply geared up and pivoted to disaster relief.

People shared information, such as where an ATM was open. The community came together to help one another from restaurants to high school kids to neighbors helping each other with water. The first cold day, the owner of an all-queer artists’ shop insisted I take, free, a gorgeous handmade rainbow beanie. It came with a hug.

Then the circle of helpers expanded. I started to seriously worry about money. I was on unpaid leave, and Elliott’s employer was closed, and he wasn’t physically ready to return anyway. Friends, family and total strangers chipped in, to my immense relief and gratitude, more than enough to ease my mind. Friends in my wife’s online trans women community helped too.

We survived, literally, for over a month on free and delicious meals cooked by local nonprofit Grassroots Aids Partnership and World Central Kitchen. I’d donated to WCK, never expecting to be a recipient.

A couple months post-storm, Elliott’s friend Jonathan summed it up: “It was a nightmare. It’s still a nightmare.” People described themselves as feeling “otherworldly” and that seemed about right.

Elsewhere now, people’s attention is off Western North Carolina, but it has years of recovery ahead and will never be the same.

The economy is extremely fragile. Many of Elliott’s friends are among the unknown but certainly substantial number of people who have left permanently because they can’t find new jobs. The storm exacerbated homelessness. In December, the governor reported 670 residences in the county were damaged, and of these 294 destroyed.

The ground itself is unstable, with highways collapsing—and confounding engineers—three months later as I write this.

It will take months or years for the muddy reservoir to return to its once pristine state. When the pipes were reconnected and (dirty) water returned to our toilet tanks, everyone rejoiced. I texted family, “I can’t wait to poop again!” When the city deemed the water clean enough for showering, it was so heavily chlorinated it burned people’s skin. But they appreciated the progress, even if they didn’t all shower in it. After two months, the water was cleared for drinking. But it still smells strongly of chlorine, and Elliott says, “Not a single person I’ve talked to is comfortable drinking it.”

After two and a half months, I was eager to return home but heartbroken to leave Elliott and Asheville. Additionally, I was worried that when I got home, with no one around who’d shared the experience, I’d feel like it was a hallucination. I needed a safe and permanent place to keep it. I needed a tattoo, and it had to be of water. Not a wave, not a drop, not a glass—a splash. A splash of beautiful, delicious, essential, fun, scary, deadly water. And I’d only get one if someone local, who’d gone through it, could do it. Chris Westhanded, who’d indeed been through it, met me at Divination Tattoo a few days before I left for home. It had been sunny since Helene, with only a few minor sprinkles. That day, fittingly, it rained hard.

More Stories

Off Broadway Feature: Audrey Heffernan Meyer in “Art of Leaving”

An Artistic Life in the Theater: David Greenspan’s sui generis career

Broadway Review: Art