He’s a man of many talents with a long career that’s included playwright, actor, director, novelist, cabaret performer, and drag icon. The legendary Charles Busch has written and started in more than twenty-five plays including The Divine Sister, The Lady in Question, Red Scare on Sunset, The Tribute Artist, The Confession of Lily Dare, and his latest, Ibsen’s Ghost.

His play Vampire Lesbians of Sodom became one of the longest running plays in the history of Off-Broadway, and over his long career, and Busch (now 69) defined the downtown theater scene throughout the 80s and 90s with his laser sharp wit, love of the classic leading ladies, and a camp sensibility.

He also made it to Broadway with play The Tale of the Allergist’s Wife, which ran for 777 performances on Broadway and racked up an impressive list of awards and nominations, not to mentioned becoming one of the longest running comedies on the Great White Way.

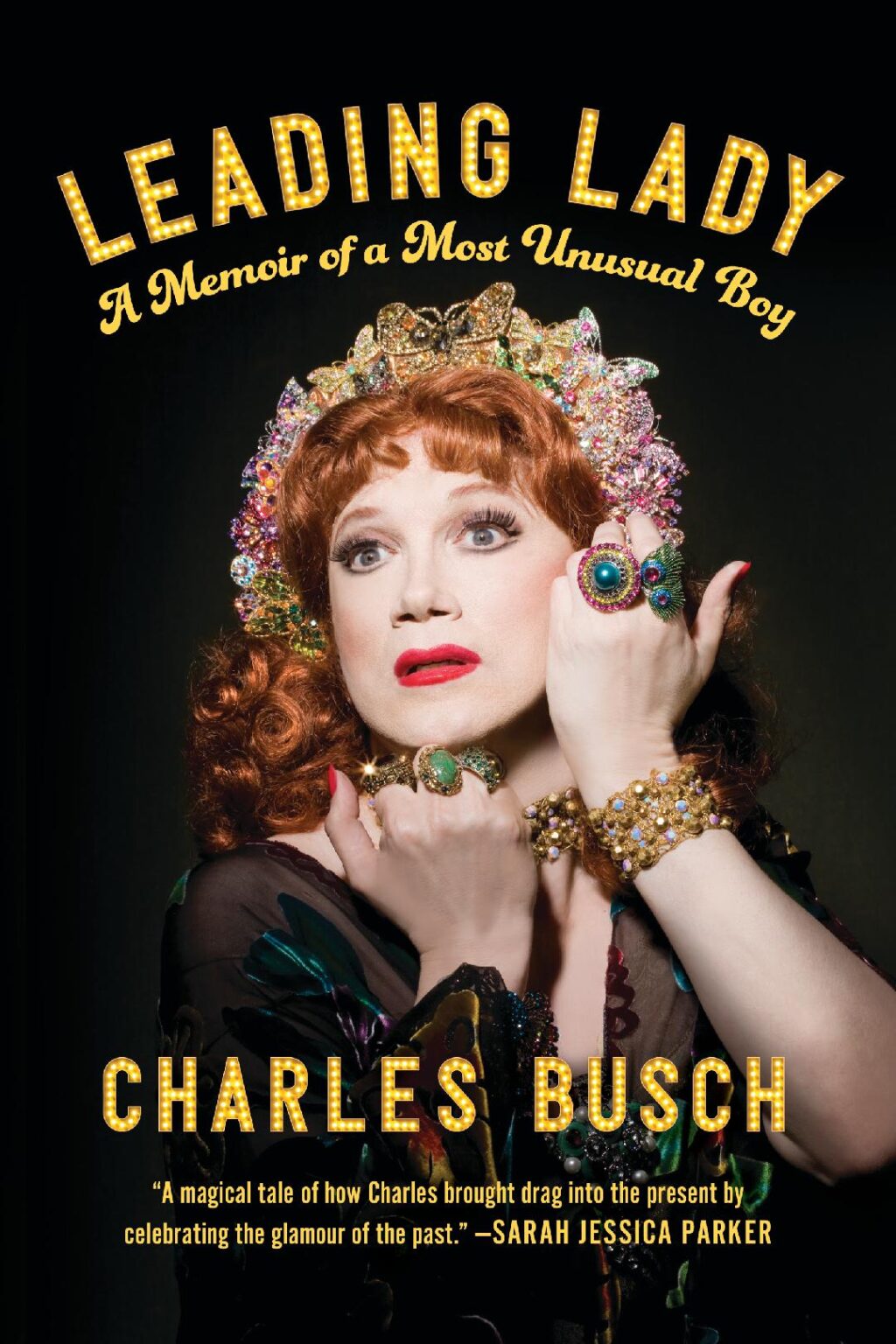

His life story, too, is quite a tale, and Busch tells it in a wonderful new memoir: Leading Lady: A Memoir of a Most Unusual Boy. Last fall, Busch talked with Connecticut Voice about his life and his memoir— the story of an artist and his quest to find and express his authentic self through his art. The book is delightful, and often laugh-out-loud funny—read. Given Busch’s work, that’s not even remotely surprising.

The book is full of stories of Busch’s childhood, which was upended when his mother died unexpectedly. Busch came under the influence of his aunt Lilian with whom he lived and who encouraged his creativity—while trying, with mixed success—to make him a better student.

Busch’s father also had a profound, if perhaps unintended, influence on the young playwright/actor’s development. After his mother died, his father, who had wanted to be an opera singer but ran a music store to support his family, went on endless dates. Busch recalls that his now-single father would come home late from “catting around with Parents without Partners,” and father and son would watch movies together, which introduced young Chares to movies and movie stars that would inspire many of his most outrageous—and deliciously campy—characters. He loved those times watching with his father, and called him a “straight man with a “stereotypical gay aesthetic.”

But Charles was always headed for the stage. “I always wanted to be on stage from early earliest memory, and I wasn’t terribly good. And, and all the way through college at Northwestern, there wasn’t any dramatic literature for, an androgynous, young gay guy. Plays like Angels in America came later.

“If I wanted to be on stage, I had to first somehow be this fake construct of sort of somewhat masculine guy. And then I had to lay the character on top of that, and so it did seem rather fake.” He adds that when he—started doing drag, he found more honesty in “tipping over into the feminine.”

The book also traces Busch’s development as an artist from solo shows, to the opportunity to produce plays on a shoestring at the Limbo Lounge and the creation of his company Theatre-in-Limbo, many of whom like actress Julie Halston became muses and collaborators over many years.

The tale also includes a rich look at Off-Off Broadway during the 1980s. It was a time of diverse and often unbridled creativity where troupes performed in bars and lofts prior to finding themselves—if they were lucky enough—in the big time of an Off-Broadway house. Busch was a central part of this movement, and as he found and developed his voice, audiences flocked to see whatever he would do next.

The book is full of stories and reflections, and as Busch said, “when you work on a book, you know, you kind of give this new view of your whole life. And, and one of the things that really amused me and, and fascinated me about my own life, was, was just that somehow I turned myself into a leading lady, right, and, and people seemed to have bought it.

“And often I end up sharing dressing rooms. I put on my makeup side by side with Carol Channing, and I’ve shared dressing rooms with Lucy Arnaz and, and Lorna Luft and Michele Lee.

“There’s, a little story in my book when I did a one-night performance of, The Women by Clare Booth Luce in Palm Springs, and it was a benefit for a theater out there. I was in drag, and I was in the rather form fitting black dress. Michele Lee suddenly said, ‘ I don’t think it’s fair that you’re miked, and we’re not.’

I said, ‘what are you talking about? I’m not miked.’

“She goes, ‘you’re body miked.’

“I said, ‘I’m, I’m not, I swear’

“And she points this area below my waist. She says, ‘I can see the mic pack.”

“I said, ‘Michele, that’s my dick.’”

You can hear the full conversation with Charles Busch on the Voice Out Loud podcast available at CT Voice.com.

More Stories

Dancing in Hard Times

Breaking Access Barriers: Connecticut’s Bold New Step Toward Mental Health Parity

Three Gay Guys Talking Cars