Gay clubs in New York proliferated in the 1990s. In fact, competition was so steep to get people to come that an entire industry grew up around trying to draw crowds. In the days before online invitations or social media, there was one medium clubs relied on: cardboard.

An entire industry that mixed art and commerce grew up, and invitations to parties were everywhere…and often in the gutter. Author David Kennerley, however, saw magic where others saw trash. Indeed, one of the less flattering names for these invites was “puddle art” because while promoters would stand outside clubs and hand them out to people as they were leaving most of them ended up tossed aside heedlessly. In his book, Kennerley notes that at the height of the 90s club scene, more than 50,000 of these cards were printed and handed out every month.

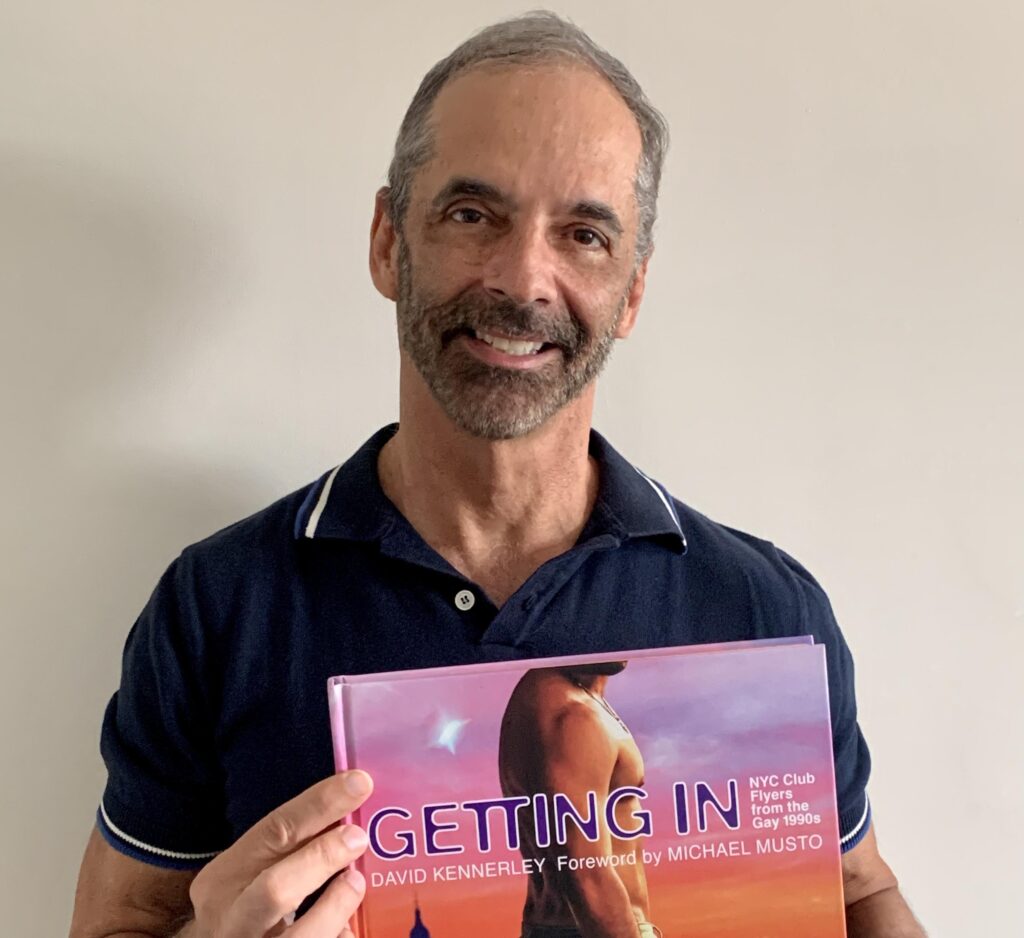

Kennerley has lovingly gone through his trove (“I’m a bit of a hoarder,” he says.) and collected the best of the best in his gorgeous book called Getting In: NYC Club Flyers from the Gay 1990s.

Kennerley chronicles the evolution of an artform as well. While the early flyers were mostly photocopied from Kinko’s, by the end of the decade, photographers were making names for themselves. Photographers like Sean Kahlil defined the era. Kahlil defined the “Chelsea boy aesthetic,” with ubiquitous promoter John Blair. Kahlil had started out photographing for Blair’s American Fitness Gym, a hotspot in Chelsea, and did invites for Splash, where these same hot boys took showers on the bar (more or less) every night.

In addition to the flyers, Kennerley has included interviews with a wide variety of promoters, photographers, and has a foreword by Michael Musto who was the de facto “Nightlife Guru” for the period from the perch of The Village Voice and his column “La Dolce Musto,” which was must-reading for all the nightlife cognoscenti in the era.

Over and above the music, the dancing, and the seemingly non-stop party, Kennerley also chronicles a very jubilant time in gay history in New York. It was a very specific time when community happened in the clubs. The dizzying dancing till the wee hours played out against a backdrop of Mayor Guiliani cracking down on nightlife, ostensibly to preserve “quality of life, but what he really did was enforce the Cabaret Law, which was hard to get and expensive…and meant people couldn’t dance in the clubs.” Guiliani’s raids spelled trouble for the clubs. At the same time, ACT UP was insisting that AIDS be addressed, and protests demanded respect and attention to the now-more-visible LGBTQ+ communities. Kennerley makes clear that the dichotomy between the need for political action and the need for community, connection, and sexual expression are not mutually exclusive. In fact, it was just this mix of glitter and grit that defined elements of gay life in the 1990s. AZT was first used to treat HIV in 1987, and understanding of sex seemed to relieve some of the anxiety of the previous years. As Musto says in his foreword, people were ready to come out from under the cloud of AIDS and party again.

In addition to the wet blanket Giuliani tried to throw on the clubs, gentrification and real estate took their toll as well. As Kennerley notes, the transformation of the Meatpacking District from dilapidated outpost to hot business and residential area pushed the clubs to Brooklyn, for one. Then the rise of apps like Grindr and Scruff, and all the hookup sites that went before, robbed the clubs of their overtly sexual and cruising element.

The clubs were a community, and Kennerley notes that in conversations with young gay men today, he senses that they feel disenfranchised, that they don’t necessarily know where to go to find the community that was so much a part of individuals discovering who they were—and who they were in the context of a culture.

The era may be gone, but Kennerley has preserved it beautifully. This is an important book both in terms of art and culture. Getting In should be at the top of your gift lists this holiday season. Order yours at www.gettinginclubbook.com.

More Stories

How Can They Keep from Singing?

“My anger problems became a success” – Artist Diane DiMassa on the Collection of her Classic Underground Comic

Dancing in Hard Times