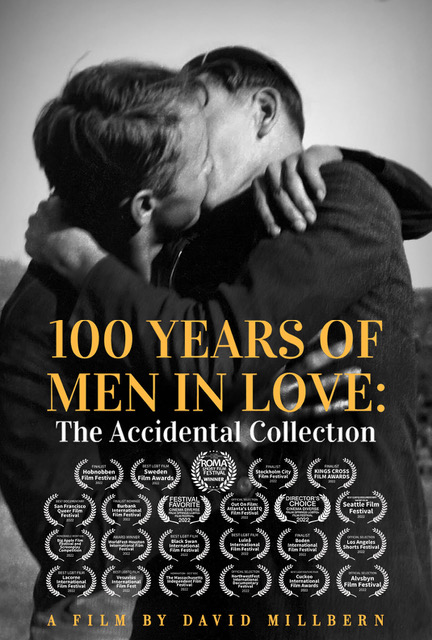

100 Years of Men In Love Documentary Shows a Century of Declarations

By FRANK RIZZO

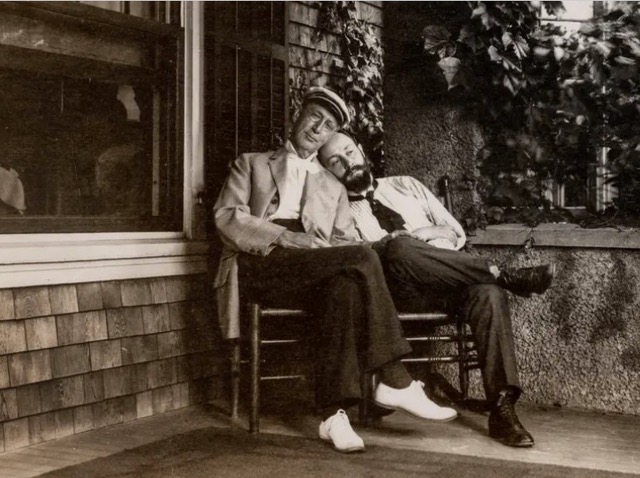

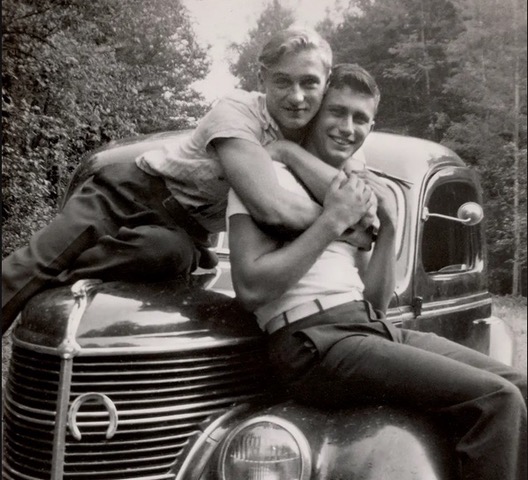

Look into their eyes, these tender young men of a century or two ago.

In haunting vintage tintypes from the 1840s, secret snapshots taken in mirrors, clandestine shoots in bedrooms, narrow strips of private images taken behind a photo booth curtain … They are all evidence that their private love existed, that it was confident and real, through their rediscovery, it endures.

A total of 350 of nearly 4,000 photographs from the collection of the married couple Hugh Nini and Neal Treadwell is the foundation of the 2022 film documentary 100 Years of Men in Love: The Accidental Collection, directed by Emmy-winning actor-producer David Millbern.

The 57-minute film is based on Nini and Treadwell’s 2020 photo book Loving: A Photographic History of Men in Love, 1850s-1950s.

Like messages placed in a bottle and tossed into the sea, these intimate vintage photographs—some joyful, some sensual, always loving—were accidentally discovered starting in the 1990s by Nini and Treadwell in flea markets, tag, garage and estate sales where discoveries were often found in shoe boxes filled with a family’s long-forgotten images. Collecting these specific photographs of male couples gradually became their passion.

Making the film

The film was made with during the pandemic without Nini and Treadwell even meeting Millbern in person with Millbern shooting scenes of the couple remotely using a New York film crew.

The power of the film comes in the contemplative relationship between the seer and the seen as the camera slowly zooms closer.

“It’s not just a quick montage of images,” says Millbern from his home in Los Angeles. “We let the audience study the photos and the significance of the times when these gentlemen put everything on the line to take those pictures. They were doing this when being a homosexual was illegal, when they could have lost their jobs.”

The film is a completely different experience than one of merely flipping through pages of a book, says Millbern.

“I want audiences to slowly immerse themselves with images of these men from the past,” he says. “I want people to be on a journey: with the film’s music; and quotations about love from gay writers like James Baldwin, Walt Whitman and Henry David Thoreau; and hearing the words taken from the backs of the photos spoken by me as these couples’ avatars come alive.

“We escalate the amount of intimacy as the film proceeds,” says Millbern. “We start with just the eyes, then body parts touching, then the men being in bed, and finally the ultimate intimacy, a kiss. That was our through-line.”

Favorite Images

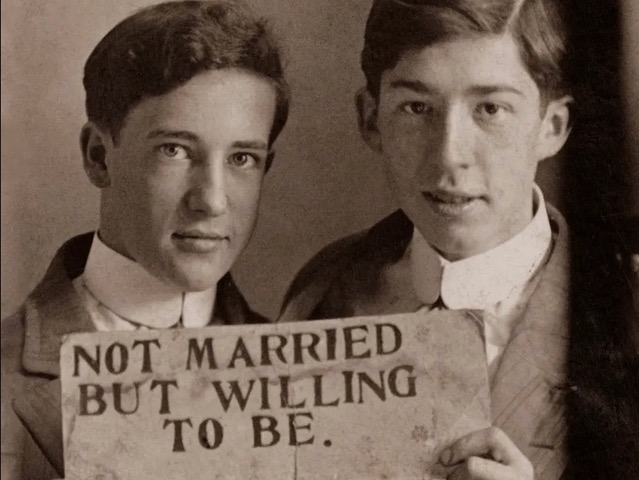

One of Millbern’s favorite pictures is one taken a century before same-sex marriage was made legal in the U.S. It was a photograph of two young men holding up a sign that says, “Not married …but willing to be.” “Did they have the vision of men marrying or was this just the momentary need of expression of their relationship to say, ‘Our love matters?’

“That picture is our superstar,” says Nini who lives in New York with his husband Treadwell. They have been a couple for 31 years.

“So many of the pictures show men clearly happy and in love,” says Treadwell. “There’s one picture taken in 1902 of two men together taking a picture in a mirror. We call it the first gay selfie.”

Millbern, Nini and Treadwell are aware of the small number of images of men of color—less than two dozen—which were all presented in the film.

“Photography at the time was kind of a chi chi thing to do,” says Millbern, “and not everyone had access to cameras and equipment, so the end result was there are many fewer of these images out there. Also remember that the stakes were even higher for these men if they were exposed.”

Nini and Treadwell never declare unequivocally that any of the men in the photographs are definitively gay. They say the images simply reflect a loving relationship between the men depicted. The rest is up to the viewer to infer.

But Nini and Treadwell have one gay confirmation by the nephew of one of the pictured gentlemen—a Johnny from Texas—posing with another soldier in the Alps during World War II. Ironically enough they belonged to “The Rainbow Division,” though the name, coined by Gen. Douglas MacArthur, did not have the gay connotation that it does today. Before his uncle’s death, Johnny revealed to his nephew a shoebox in the closet that included the photo of the two men together along with a gold ring. Johnny told the nephew, ‘Please keep these safe after me,’” says Nini, who adds the nephew now wears the ring in memory of his uncle.

Clues of relationships can come from surprising places. On the back of a color picture from the early 1950s is written—perhaps by someone’s wife: “Here’s a picture of Bob and his friend. Bob loved horses. Your dad says they were both as queer as ducks.”

Sometimes the clues are directly from the men pictured. Another photo shows two men on a carriage pulled by a horse and on the back is hand-written: “Here’s a glimpse into a little part of my life that you may not know about.”

“Now doesn’t that say it all?,” says Millbern. “It’s up to the viewer to imagine relationships, but it’s very clear that there was something going on with the men in these photographs.” He points to the famous Kinsey scale which measured different degrees of same-sex attraction.

Other clues that indicate a more personal context is in the use of a romantic photographic trope of the late 19th and early 20th century: Being pictured beneath an umbrella or parasol. There are multiple images of men huddled beneath the intimate covering, shoulders touching, fingers brushing against each other on the handle just so, with the couple having a private or playful moment. “The images of two men beneath an umbrella was a kind of a rainbow flag in the late 1800’s,” says Millbern.

Future life

The film was presented at Palm Springs this past spring, and further museum and festival presentations are planned for later this year and into next. There will also be a touring exhibition of some of the photos with its first stop in Geneva, Switzerland in June. Several high-profile museums have also reached out to the men interested in their archives.

“The pictures have now taken on a life of their own,” says Treadwell, who adds a follow-up volume is in the works.

An earlier book published in 2000—Dear Friends: American Photographs of Men Together, 1840-1918, by David Deitcher—also takes intimate and vintage photographs of men but places the often more ambiguous images in a broader context of male relationships.

Nini says he’s sure these men never imagined their clandestine, loving, joyous photographs being seen and appreciated in 2023. “I’m sure they’re looking down and going, ‘Holy shit. Our photographs are in books and in a movie.”

“We feel someone is looking over our shoulder,” says Treadwell.

Millbern says he hopes the film is a call to action for new generations of gay men.

“If these guys faced imprisonment, loss of employment and a complete dismissal of their lives, yet still created these images to document their love, we have to be bold, too,” he says. “We stand on the shoulders of these gentlemen who said their love mattered. It should be an example for the rest of us to be authentic, too.”

More Stories

Broadway Review: Art

Fall Arts Preview: Emus, Foxes and Eric Clapton, Too

Diane DiMassa Book Event September 25