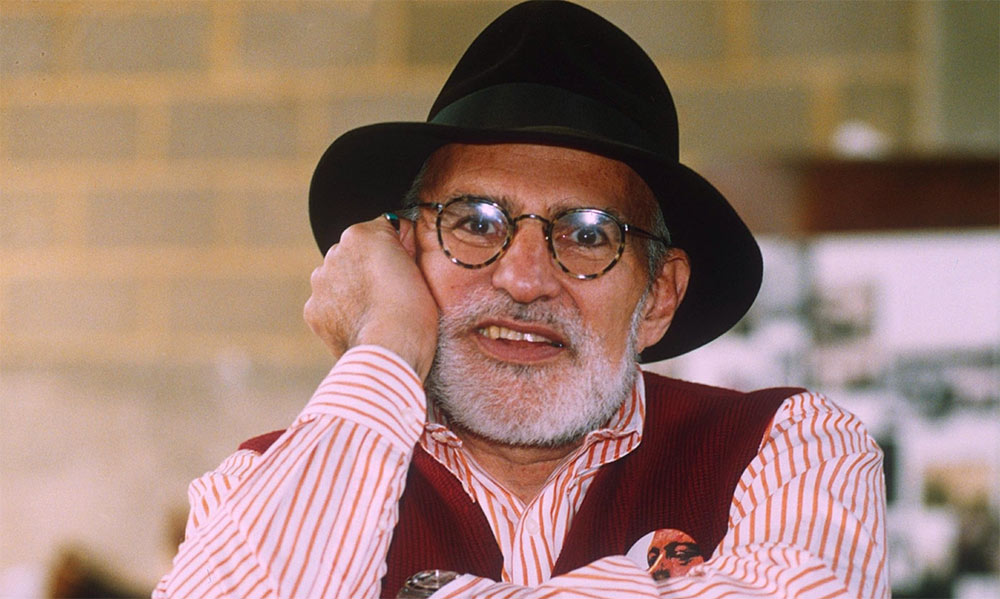

Larry Kramer (1935 – 2020)

Sounding the alarm, fighting for rights

By Frank Rizzo

Seeing Larry Kramer’s primal scream of a play “The Normal Heart” when it premiered in April of 1985 was a passionate, heartbreaking, and harrowing experience I’ll never forget.

The play was meant to be an in-your-face polemic with no place to hide. Theatergoers were surrounded by walls scrawled with the names of those who died of HIV/AIDS. Set in the early days of that pandemic, which decimated the gay community, the play followed writer Ned Weeks – an outspoken, exasperating gay man who, like Kramer himself, found himself rising to a historical moment in a role for himself he had never envisioned.

In the play – and in life – Kramer boldly named names, calling out New York City Mayor Ed Koch, President Ronald Reagan, The New York Times and even the gay community itself, for its lack of action in the face of the growing scourge. He was the living embodiment of the war cry of the era: “Silence = Death.”

At that point, the disease had taken tens of thousands of lives. Hundreds of thousands more would perish in the United States, and millions more globally, by the time the play was revived in 2004. When the drama finally made it to Broadway in 2011 in a Tony Award-winning revival, and later became a television movie on HBO in 2014, AIDS no longer made headlines. It was an increasingly distant memory for some, and for a new LGBTQ generation, it meant hardly anything at all.

Larry Kramer, the Bridgeport-born, Yale University-educated writer-activist, died May 27 at age 84 of pneumonia.

I interviewed Kramer several times over the years at his Manhattan apartment off of Washington Square, a home that he shared with his husband, David Webster. My first visit was in 1986, when New Haven’s Long Wharf Theatre presented its own production of “The Normal Heart” starring Tom Hulce (Academy Award nominee for “Amadeus”).

“Now AIDS has a human face,” Kramer told me at the time.

With a scruffy beard and big brown eyes, Kramer could be gruff, relentless, and exhausting but he was also inspiring and, yes, funny and charming, too. He was a teddy bear with teeth.

Kramer first found success in his early life in Hollywood as a producer and writer, earning an Oscar nomination for his screenplay for 1969’s “Women in Love,” based on the D.H. Lawrence classic. (And what gay man then will forget the homoerotic nude wrestling scene by firelight between Oliver Reed and Alan Bates?)

Kramer was a novelist, too, challenging norms – and other gay men – with his 1978 novel “Faggots,” which pulled the curtain to reveal the gay community as he saw it, and it wasn’t all pretty.

“We should get people – and ourselves – to stop defining us by the sexual acts that we do,” he told me.

In 1982, shortly after news began spreading of a “gay cancer,” he co-founded Gay Men’s Health Crisis (GMHC), the nonprofit AIDS service organization. (Kramer resigned in 1983 due to his many disagreements with the other founders.)

An article Kramer wrote in 1983 for the New York Native, titled “1,112 and Counting,” was a further wake-up call. “If this article doesn’t rouse you to anger, fury, rage and action, gay men have no future on this earth,” Kramer wrote.

In 1987, Kramer founded the grassroots, more militant group, ACT UP (AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power), which took to the streets demanding an acceleration in AIDS drugs research and an end to discrimination against gay men and lesbians. Both organizations he started reshaped national health policy in the ’80 and ’90s.

By his own accounts, he should never had lived as long as he did. He was HIV-positive since the ’80s, and in 2001 he was dying of a liver disease until a transplant allowed him to live into the third decade of the 21st Century.

In a memorial piece written for The Guardian, playwright Matthew Lopez (who wrote the epic “The Inheritance,” which spans several generations of gay men) recalled a panel that included Kramer last year celebrating the 50th anniversary of the Stonewall riots. When asked about the importance of that now-hallowed 1969 event, Kramer said it wasn’t important at all. One can imagine the gasps and the clutching of pearls.

But that was Kramer. Deliberately contrarian, wanting to shake people out of complacency and easy narratives. Though Stonewall brought visibility, it did not bring meaningful change, he said, adding that it took the scourge of AIDS to turn gays queer, and to launch an unstoppable political movement around the globe.

His mantra throughout had always been that until gays came out of the closet, until people recognized the LGBTQ community – not in the abstract or as “the other,” but as their sons and daughters, brothers and sisters, fathers and mothers, friends and neighbors – meaningful change would not happen.

Larry Kramer was right – absolutely – and millions of LBGTQ people living today, survivors and descendants alike, owe him their eternal thanks.

More Stories

Broadway Review: Bug

Off Broadway Feature: Audrey Heffernan Meyer in “Art of Leaving”

An Artistic Life in the Theater: David Greenspan’s sui generis career