Author tells tales of history, Hollywood,

and life through a gay lens

By Frank Rizzo

Best-selling author, professor, activist and chronicler of gay life, celebrity and history for more than 35 years, William J. Mann remembers an incident in 1991 when he was still in the closet to his family – even though he was co-editor of Metroline, Hartford’s periodical for the gay community.

At the time, he was covering the passage of a gay civil rights bill at the state Capitol for Metroline.

“The crowd was cheering, chanting, ‘We won! We won,’ and I’m there writing it all down,” says Mann from his office at Central Connecticut State University in New Britain, where he teaches history. “A reporter from the Hartford Courant came up to a group of us and asked for our names and I thought, ‘Please don’t publish my name because I haven’t come out to my parents.’”

But hadn’t he had been writing for and editing Metroline at that point for several years?

“My parents never read Metroline,” he says, smiling, “but they did read the Courant, and not only was my name in the paper but also my photo. I called my parents and said, ‘Umm, yeah that’s me.’”

And the reaction?

“It didn’t go well at first. My father was city treasurer in Middletown and once ran for mayor. My mom worked at the Superior Court and my older brother worked for [former U.S. Senator] Chris Dodd. We were a very political-type family, and there was my face in the Courant as ‘the gay guy.’”

But family attitudes gradually improved so much “that within five or six years, my parents were basically PFLAG people. They both ended up loving my husband, coming to our wedding in P-town, and my husband and I were with my mother when she died. That’s how close we all became.”

“I liked boys.”

Mann says he knew he was gay growing up in Middletown “as soon as I learned the word ‘homosexual,’ which was probably in the fifth grade or so. I knew then what I was. I liked boys. It’s interesting now because I have so many students who identify as nonbinary or trans but I never questioned my gender. I always liked boys and I always felt very boy-ish.”

Mann, 58 – and still retaining the boyish charm – received his undergraduate degree at CCSU in 1984. He followed that with his master’s degree from Wesleyan University in Middletown in liberal studies with a concentration in history and film, graduating in 1988. He met his husband, psychologist Dr. Timothy Huber, in 1988 and they have been married for the past 15 years.

“I had a game plan,” says Mann of his life then. “I wanted to write books and, at the time, I really wanted to write novels.”

Metroline gave him his first bylined story – and a taste for advocacy journalism, too. Within a few years, he and Sarina Kahn, a Pakistani Muslim lesbian, were running the magazine – first as co-editors and later as co-publishers at a time when the AIDS epidemic and the fight for gay and lesbian civil rights and visibility was at its height in Connecticut and nationwide.

“It was a transformational period and we were covering it all,” says Mann, who also co-founded the first gay film festival in the state in 1987, Out Film CT.

But the emotional and financial pressures at Metroline eventually took their toll. “Sarina and I never got any money for doing Metroline. We couldn’t, because we had to pay the staff and to keep the thing being published. I had a boyfriend, now husband, who was working but I don’t know how Sarina got through it. And all during this time, friends were dying all around us.”

Escape to P-town

Many who were ill relocated to a supportive gay community in Provincetown, Mass. In the mid-‘90s, Mann left Metroline – and Hartford – and relocated there, too.

“A good friend of mine, Victor D’Lugin, was very sick. He was a professor of political science at the University of Hartford and he was one of the [first] activists I met. He was a huge influence on me and my husband. He taught me in some ways how to be gay and how to stand up for who you are.”

Mann and Huber cared for D’Lugin until his death in 1996, just missing the emergence of azidothymidine, the drug more commonly known as AZT, which gave many with AIDS a new lease on life.

“By that time, I’d fallen in love with P-town and I knew I wanted to make that [place] part of my life,” he says. He and Huber still have a home there, as well as residences in Milford and Manhattan.

While on the Cape, he began writing his gay-themed novels, first with 1997’s “The Men from the Boys,” followed by “Where the Boys Are” in 2003, both set in Provincetown; then with “All American Boy” in 2005, “Men Who Love Men” in 2007 and “Object of Desire” in 2009.

He segued into the world of non-fiction with a series of Hollywood-based books. In 1998, he drew widespread attention with “Wisecracker: The Life and Times of William Haines,” writing about a leading man of the 1920s and ‘30s who was Hollywood’s first “out” star. Mann earned the Lambda Literary Award for the book.

That was followed by “Behind the Screen: How Gays and Lesbians Shaped Hollywood, 1910-1969” in 2001, and “Edge of Midnight: The Life of John Schlesinger” in 2005.

Mann reached mainstream readers with his insider celebrity biographies, exploring the early fab of Barbra Streisand (“Hello, Gorgeous: Becoming Barbra Streisand”), a revealing portrait of a nonbinary Katharine Hepburn (“Kate: The Woman Who Was Hepburn”) and the allure of Elizabeth Taylor (“How to Be a Movie Star: Elizabeth Taylor in Hollywood”).

Mann hit the best-selling lists in 2014 with the movie capital crime saga set in the 1920s, “Tinseltown: Murder, Morphine, and Madness at the Dawn of Hollywood.” The book won Mann the Edgar Award from the Mystery Writers of America. It’s now in development for television.

“I’m a historian and that’s my strength. I love research and digging into old records. But all the books I’ve written, there’s been something gay in all of them. Even the Roosevelts with Eleanor and a few of the nephews,” he says referring to his last book, “The Wars of the Roosevelts: The Ruthless Rise of America’s Greatest Political Family.”

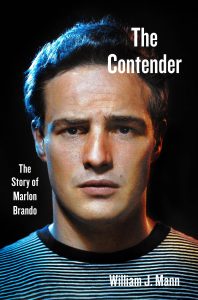

Taking on Brando

For his just-published book, “The Contender,” Mann takes on Marlon Brando, who died in 2004 at the age of 80.

“I tried to see him in a different way and go beyond the Hollywood image and the stereotypes.”

And how did Brando, whose career exploded in the late ‘40s and never stopped, view homosexuals?

“In various interviews in the ’70s he would say things like, ‘Now the homosexuals are claiming rights, and this is a country about people coming forward and claiming their rights.’ He was seeing the gay movement as part of the civil rights movement. But Brando did not take a participatory role in the gay rights movement as he did in the African-American and Native American civil rights movements,” says Mann.

“He very specifically talked about his own [same-sex] experiences. He said as part of a larger interview, ‘Like many other men, I have had these experiences and I feel no shame in it.’ But he didn’t see himself as a homosexual – and I don’t think he was. He was a heterosexual who was fluid. His only ongoing male relationship was with [French actor] Christian Marquand. They were buddies who sometimes fooled around, and sometimes that included with women as well.”

What would Brando, who abhorred publicity and attention on his private life, have thought of Mann’s book?

“He didn’t like people writing about him or analyzing him. But Mike Medavoy, the film producer who was one of his executors, said Brando would have appreciated this effort. At least I tried to understand his point of view, which no one ever did before. But I’m sure he would also say, ‘You’ve got this wrong,’ because he was also someone who was constantly trying to rewrite his own story.”

As a historian, Mann often is included as a source in other people’s books and documentaries. He is featured in the 2017 documentary “Scotty and the Secret History of Hollywood” about Scotty Bowers, who died this fall at age 96. Bowers allegedly arranged secret sexual liaisons for the stars for decades beginning in the ’40s. “I believe him 100 percent,” says Mann. “I went to Gavin Lambert, one of the great Hollywood historians, and Dominick Dunne, who knew everybody and everyone, and I asked them if I could believe Scotty and they said, ‘Yes, believe him.’”

Reaching a New Generation

Mann says “Tinseltown” is being developed for network TV but, for the first time in years, he doesn’t have a book project ready to go. He has another year in his contract to teach at CCSU but isn’t sure what lies ahead beyond that.

But his time at the university has been invaluable to him, surrounded by “Generation Z” students.

“Our generation has failed somewhat in communicating our [LGBTQ] history to them. I took 11 students to NYC last spring for a Stonewall history tour and I led them around the Village, Chelsea, and all sorts of places like that. Seeing the way that the students looked at these things and listened to these stories…,” Mann says, his voice trailing off. “I know this sounds corny, but it does give me hope. This is a generation that has been brought up to say, ‘We matter just as much as anyone else.’ This is the Parkland student generation and their attitude is, ‘What do you mean I can’t do this because of the color of my skin, or because I’m gay, or because of my gender identity?’ It’s unthinkable to them and, ultimately, that power is going to rise to the surface.”

A little oppression goes a long way because it forces you to create these cultures, communities and alternative safe spaces. It’s a little sad for me as a gay man because I see my culture – the culture I loved so much and that nurtured me – kind of disappearing.

But as some things are lost, there are also gains.

“They are not gay and lesbian kids in the way we were, and they see their world differently, they live in the world differently, they identify differently. They don’t need to go to P-town the way we did. That’s not a big draw for them,” Mann says.

“That doesn’t mean they don’t face discrimination. They certainly do. It’s just that they interact with the world differently. But we have to find a way to connect with them because we have so much history we can share so they can understand how we got to this point. That’s why these last two years [at the university] have been so important to me – because I realize that that’s something I can do.”

More Stories

Broadway Review: Art

Fall Arts Preview: Emus, Foxes and Eric Clapton, Too

Diane DiMassa Book Event September 25