50 years after the riots, some of us haven’t stopped fighting

By Dawn Ennis

Millions of people, from Connecticut to all over the world, will flock to New York City in June to march, dance, sing, and simply celebrate Pride, amid the traditional stream of rainbow banners and flags. This summer’s annual observance is sure to be different, however, as gays, lesbians and other members of the LGBTQ community take to the streets to mark the 50th year since another generation did so. Then, it was in violent protest of their inability to freely express their sexual orientation and gender identity.

“Stonewall was a pivotal event in human history,” said Jason Victor Serinus, a music critic and former New Haven activist of that era. “An oppressed minority said, ‘Enough! Stop! We’re not going to take this anymore.’” It was a late Friday night, or early Saturday, June 28, 1969, when an uprising broke out against baton-swinging police officers who raided The Stonewall Inn in New York City’s Greenwich Village. The crime? Alcohol was being served there without a license. And men were dancing with other men. This wasn’t the first time police had launched a raid, but unlike other times, this one wasn’t anticipated – the mafia-owned dive bar was typically tipped-off in advance of police action – and on this night, the raid unexpectedly erupted into violence.

Some gay men refused to show their driver’s licenses to cops, for fear their families would find out their secret. Male officers reportedly groped the handful of lesbians at Stonewall, in the guise of searching them, and arrested all who could not or would not provide legal identification. Women were required to prove they were wearing at least three pieces “feminine clothing.” However, women’s clothes worn by drag queens and transgender women, who were then called “transvestites,” were grounds for arrest, as was lacking proper ID.

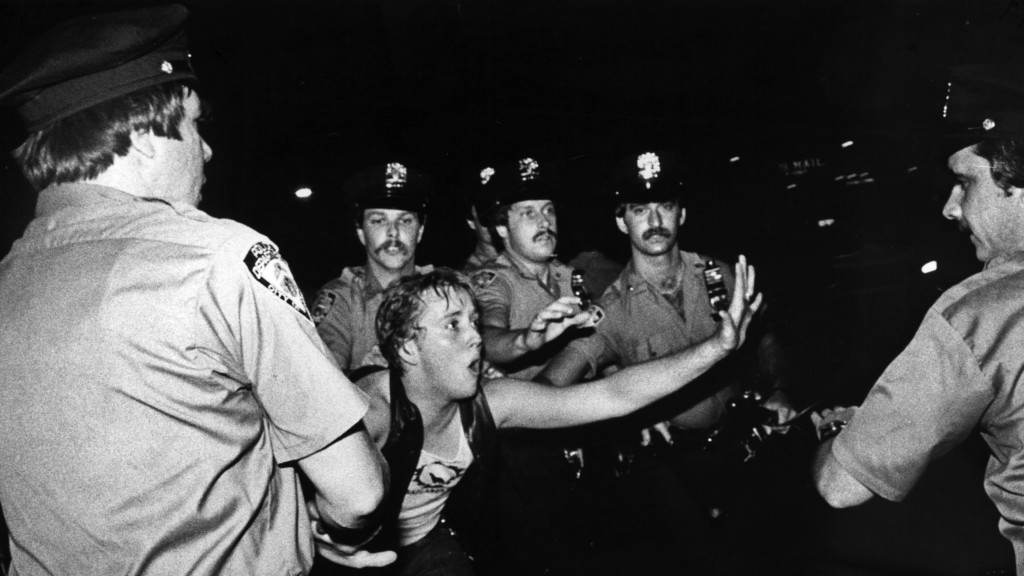

As the eight detectives, two of them women, waited for vehicles to haul away some of the 13 suspects they had rounded-up, a crowd standing in the hot summer air outside Stonewall began to grow, both in number and in frustration. According to blogger Keith Allison, one anonymous Stonewall customer was quoted as saying, “This shit has got to stop!” Instead, the shit hit the fan. A policeman hit a butch lesbian named Stormé DeLarverie over the head for saying that her handcuffs were too tight. Seeing this, and hearing her shouts for help, a woman in the crowd named Sylvia Rivera threw a bottle at police; a Stonewall patron named Marsha P. Johnson and other drag queens as well as the crowd of men joined in.

They threw everything at police that they could get their hands on, evencoins. Outnumbered cops retreated inside the bar, as hundreds protested outside, banged on its doors and tried to burn down The Stonewall. The clash between the N.Y.P.D. and beer can-tossing, bottle-throwing, cobblestone-hurling protesters sparked several nights of riots across the Christopher Street neighborhood surrounding that now-famous tavern. News of the riots inspired even bigger protests, lasting six long days and nights.

The slow march toward equality over the five decades since Stonewall will be commemorated on Sunday, June 30, at what is now a national historic landmark. History took its time traveling more than 80 miles from The Stonewall to New Haven’s then-burgeoning gay community. In June 1969, Jason Serinus cruised the streets around Yale University and worked in the Sterling Memorial Library on campus. Those days remain fresh in the mind of Serinus, now 73. “It was like no other time,” the journalist and professional whistler told CT Voice. “I remember going past The Pub, the gay bar in New Haven, which was affectionately known as, ‘The Pube,’” he says. A 2001 story in the Yale News called the long-gone watering hole “a meeting place for gay Yalies for nearly 60 years” and a necessary aid in the gay dating world of the past,” when being openly gay could spell disaster.

That’s also where Serinus first came out, to end what he called “the darkest memory, my own fear and self-loathing,” by walking inside for the first time. Serinus says he remembers vividly the newsstand outside The Pub, where one day he spotted the front page of the now-defunct Village Voice, telling the story of the riots at The Stonewall Inn.

“The forces of faggotry” led to a “kind of liberation,” Lucian Truscott IV wrote in the July 2, 1969 issue. “Limp wrists were forgotten. Beer cans and bottles were heaved at the windows, and a rain of coins descended on the cops.” From inside The Stonewall, Howard Smith huddled with police as he wrote for that same issue of the Village Voice: “By now, the mind’s eye has forgotten the character of the mob; the sound filtering in doesn’t suggest dancing faggots any more. It sounds like a powerful rage bent on vendetta.” Some protesters reacted so angrily at those loaded words that the rioters targeted the newspaper itself. In some ways, that rage has not faded much in the 50 years since Stonewall. It fuels how some members of today’s LGBTQ community feel about police, especially in regard to their participation in Pride events.

“The police have been monsters,” says transgender activist Miss Major, who was at the Stonewall Inn the night of the 1969 raid. In a public service announcement posted to Twitter in January by Gay Shame’s Five-O Out of Pride 50 campaign, Major declared police officers should be banned from marching at all Pride celebrations. “They’re all worthless, unimaginable, horrible people and destructive to mankind in general, especially to my trans and gender-nonconforming community,” she wrote. As to those who welcome officers who identify as LGBTQ, who wave rainbow flags as they march, Out magazine reported Major is clear on her position: “Fuck a flag,” she said. “That shit doesn’t mean a damn thing if you’re not going to treat people right or fair or honestly.” She’s not alone; the meme “No Cops at Pride” has gained traction in recent years, as the website them reported. The group No Justice No Pride issued demands in 2017 to organizers of the Capitol Pride march in Washington, D.C., to avoid a repeat of a parade-stopping protest the year prior. Among the demands, they insisted that the event “stop celebrating the police,” even out of uniform.

“At the end of the day, NJNP doesn’t want a formal cop presence in the parade,” Jacinta told NBC News. “We look at our history and our present reality and see there is very little accountability for the extrajudicial murder of civilians, especially brown and black folks.”

The LGBTQ community in particular has a horrendous record in its dealings with law enforcement, according to the Williams Institute at UCLA. Nearly half, 48%, of all victims of anti-LGBTQ violence reported that their interactions with police had resulted in misconduct, unjustified arrest, use of excessive force, and entrapment. The numbers are higher among all groups that are LGBTQ and minorities, the researchers found, with two-thirds of transgender Latinas reporting verbal harassment, and one in four suffering sexual assault by officers of the law.

So, seeing an officer in uniform at Pride or anywhere can be triggering for many. But for others, seeing a cop with a rainbow flag is a sign of how far gays have come. “This isn’t 1969, those cops [from The Stonewall riots] aren’t on the force any longer,” says Officer David Hartman of the New Haven Police Department. “Several years ago, I myself marched in the New Haven Pride Parade and several of us attended the Pride event downtown.”

Hartman said his top brass want their officers to participate, whether they are LGBTQ or not. “The NHPD would allow any officer to attend and participate in a Pride march or related LGBTQ event,” wrote Hartman, in an email to CT Voice. “Such would be no different than an officer marching in the St. Patrick’s Day Parade or anything similar.” There are rules that govern uniforms, but what about complaints that uniformed police are unwelcome at Pride events? “Honestly, we don’t care – or should I say – we can’t possibly juggle the opinions of everyone,” Hartman responded.

“Having attended Pride events in many communities – Connecticut and elsewhere – I’ve witnessed many more cheers when LGBTQ or supportive officers march by than gestures of disapproval,” said Hartman. “The climate of policing has changed drastically for the better, though further change is welcome and continues to be needed.”

Change was swift in New York City, where a militant band of gays organized the very first NYC Pride march in 1970. They had come together just weeks after the riots to form the Gay Liberation Front. That, in turn, inspired a Methodist minister on the Yale campus to suggest Serinus spearhead New Haven’s own chapter. From there, Serinus expanded his horizons, moving to New York’s historic 17th Street Gay Men’s Collective. He says a popular phrase from that time, from the Bob Dylan song It’s Alright, Ma (I’m Only Bleeding), still applies today: “He not busy being born is busy dying.” “This is a time for everyone to be busy born anew, in the most wholesome of senses, to realize our potential. We need to remember the people who fought, and did so bravely, and said, ‘Enough!’ They did not bottle up their anger, but instead they channeled it into constructive action,” says Serinus, concluding: “That’s what I’d like to see happen” as New Haven and the world remembers Stonewall.

More Stories

Looking Back

Take a Tour of Gay New Haven

Eloise Vaughn Worked her MAJIC