Playwright Jeremy O. Harris looms large as he talks about the past – and the future

By FRANK RIZZO

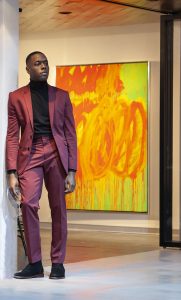

At six-foot-five, sporting a towering Afro and wearing a mustard yellow Acne Studios denim outfit and black Doc Martens, Jeremy O. Harris could stop traffic – or at least act as a warning to proceed with caution.

His two plays that premiered this past season in New York, “Slave Play” and “Daddy,” have proclaimed just as boldly that this queer, black playwright is someone to be reckoned with as he explores taboo subjects of sex, desire and race.

“There should be a 13th astrological house created to be able to comprehend him,” says James Nicola, artistic director of New York Theatre Workshop who put ‘Slave Play’ on the fast track to production last year. “It would be the House of Theatrics. Almost no one I’ve met has such a vibrant, innate impulse to dramatize, to tell a story. When we first encountered ‘Slave Play,’ this is what immediately struck me – his outrageous theatricality, coupled to his wit and his compassion.”

Arriving at Heirloom Restaurant in New Haven for this interview, his physicality is imposing at first but immediately softens with his broad, welcoming smile, warm exuberance, and casual chat about mutual acquaintances.

Throughout the burger-and-Coke lunch, Harris speaks with the speed, fluidity and flourish of a supremely confident young man on the run, dashing to meet deadlines and confounding expectations, while dodging people and policies that stand in his way. He speaks with humor, charm and frankness about a wide variety of subjects, including his experience at Yale School of Drama, his outlook on the changes in American theater, and his plans to live in Berlin, Germany.

In May, Harris, who turns 30 in June, graduated from the three-year graduate playwriting program at Yale School of Drama. While that would be seen as a career launch for most students, Harris is already in full orbit.

Last fall, his “Slave Play” was fast-tracked at the New York Theatre Workshop and received the kind of reviews that emerging writers dream about.

Jesse Green, writing in The New York Times, called it a “willfully provocative, gaudily transgressive and altogether staggering new play. … [Harris] writes as if he’s known all his life how to twist audiences into all kinds of pretzels. In particular I can say as a white person that he manipulates white discomfort expertly to the advantage of his storytelling. Until I encountered his potent brew of minstrelsy and melodrama I hadn’t known it was possible … to cringe and laugh and blush at the same time.”

Earlier this year, his second play of the season, “Daddy,” premiered at off-Broadway’s The Pershing Square Signature Center. A co-production of the New Group and Vineyard Theatre, the production starred Alan Cumming, Ronald Peet and a 27-foot by 10-foot downstage pool. The play centered on an emerging black artist and an older, wealthy white art collector and explored their complex relationship, dealing with role play, race, religion, the art world, and daddy issues. While it did not receive another critical embrace, it was undeniably ambitious and mesmerizing as it traveled its ever-twisting, psycho-sexual path.

“I’m not a cubbyhole guy,” Harris says. “I don’t know how to be. I’m such a baby of the Internet that I have to be over-stimulated to stay on topic.”

This fall his new play – “A Boy’s Company Presents: ‘Tell Me If I’m Hurting You,’” billed as a revenge fantasy that centers on the relationship between two young men – will be produced at off-Broadway’s Playwrights Horizons. Another new play also is slated to bow next year at off-Broadway’s Vineyard Theatre that Harris describes as “‘The Colored Museum’ on crack.” He has several film projects, too, including a screenplay for “Zola” that he co-wrote with Janicza Bravo, based off the epic Twitter thread. Another film script is in development with producer Bruce Cohen (“Milk,” “American Beauty”). Broadway producer Scott Rudin has also commissioned two plays from him as other theaters wait their turns.

He is exiting Yale in voice-to-power style in a production at the Yale School of Drama’s Carlotta Festival of New Plays (the annual showcase for third-year playwriting students) that is sure to make some cheer and others squirm in their seats.

Finding His Voice

Harris spent much of his early life in Martinsville, Virginia. His mother, a single parent, was a hairstylist and it was in her salon where he became “socialized in this hyper-queer space. And I mean queer in the sense of the things that the women in my mother’s community talked about, such as the disparate politics that mark a true queer spirit. All of this was engendered in me at a very early age.”

“It’s a surprise to a lot of people who know my work, but my queer identity was more of a social than a sexual one for most of my childhood and teenage years,” he says. “I ended up going on this weird ride where I was socially hyper-queer but I dated girls. I didn’t know I actively liked boys.”

Harris was a voracious reader and an autodidact at an early age. He read, at the suggestion of a drama teacher, all the Pulitzer Prize-winning plays in an effort to know more about the theater. When he discovered that Marquis de Sade shared the same birthday (June 2), he decided at age 12 to read the author’s “Philosophy in the Boudoir.” But he also read and memorized major chunks of the Bible.

When asked if he was ever bullied as a kid, Harris says he was, “but everyone was, and I was also a bully, too. If I was bullied for anything, it was less so for being queer and more so for being pretentious, being the know-it-all who was also fey – that can go under the umbrella of ‘faggot.’ But for me, the reason you’re being called a faggot is that you’ve read all the books on the accelerated reader list. That’s what pisses people off. Whenever I was bullied, it was from people who I could immediately bully back because they weren’t smart. I was always surrounded by a clique of other kids who were into me being pretentious: the reading crowd. I joke that I don’t make friends with people who don’t read. All my friends here are people who read – a lot.”

It wasn’t until he went to DePaul University in Chicago that his queerness “took on less of a social lens and more of a physical one. In college, I had this moment at the end of my freshman year and it was like, ‘Oh, I’m gay.’ It was like an immediate recognition. I told my friends and it was very little Sturm und Drang. Two months after I came out to my friends, my mom said she felt l had a secret and I said, ‘Well, I’m gay. I like guys.’ She said she thought so but wasn’t sure. She was totally fine with that.”

He left DePaul after his first year to go to Los Angeles and eventually his paths crossed with Isabella Summers of the band Florence + the Machine, who said if he wrote a play, she would compose the music. He did, and “Xander Xyst, Dragon 1,” about a Grindr date with a straight porn star, was presented at a New York theater festival where he became hooked on writing for the theater. That was followed by an invitation to the MacDowell Colony, where in 2016 he wrote “Daddy.” That play proved to be a factor in getting accepted into Yale. While in New Haven, he wrote “Slave Play.” Both works deal with legacies of white supremacy and the complex issues of black identity.

The Yale Years

When he was told he could not direct his proposed work for the Carlotta Festival, Harris withdrew it and wrote a new play that might make some at Yale cringe with its frankness about his experience there: “YELL,” subtitled “a ‘documentary’ of my time here.”

“It’s a rage play about what it means to be in an integrated education system my entire life, and the play asks, what does that do to the psychic life of a black queer person — and what’s that like here at the Yale School of Drama?”

Harris says his Yale experience is a complicated one.

“I thought the artist I articulated that I wanted to be when I came here, which was a political artist, would be super nurtured here,” he says. While he says allowance for that kind of work was often “great and amazing,” he had doubts if he received “the tools to facilitate interdisciplinary conversations” for the kinds of works he wants to do. He felt limited in breaking through to Yale’s other “academic silos” but still managed to find his own connections and colleagues at the schools of art, architecture, divinity and music.

“It’s been a really interesting push and pull because, like most institutions, they can’t completely say no to any student with enough ambition and will. But the emotional toll that it takes in getting the thing you need or want is a mess,” says Harris.

For example, during his first year, he put on “Water Sports; or insignificant white boys,” an unsanctioned, interactive production, during a school break and staged it at the art gallery.

“So much of the pedagogy here is centered on a production model that mimics the production model of Yale Rep. And if your work doesn’t work inside that model, then you’re sort of left out in the cold,” he says.

Relationship With McCraney

Also “complicated” is the arrival of Tarell Alvin McCraney, an American playwright and actor who came in for Harris’ second year to head the playwriting program. McCraney, who graduated from the Yale School of Drama’s playwriting program 12 years ago with a similar buzz to what Harris is experiencing, won with Barry Jenkins the 2017 Oscar for Writing (Adapted Screenplay) for “Moonlight.” He made his Broadway playwriting debut with “Choir Boy” this season and has created a new series for Oprah Winfrey’s network this summer.

As Harris describes it, “It’s been a very difficult transition going from having a person who very much took care of us because she chose [the three students in the class]. “I’m not sure [McCraney] would have chosen me. He was also someone who was having a lot of balls in the air. But I think there are things that have been so great about having someone like Tarell here — and who has had such a similar trajectory as me.”

He adds: “But that’s one of the dangers of identity politics. It flattens things. One of the professors here who has understood the work I’m doing the best and whom I feel I connect to the most is [playwright] Amy Herzog, a white woman but her relationship to text is very similar to mine.”

Harris says he’ll be living in New York after graduation for a while, “before I go to Berlin for my new life.

I don’t know if I want to stay in America and be a playwright. I just find it limiting sometimes and there’s not as much space for growth.”

Was this a serious plan or more of a notion? Before I could follow through with my question, he was dashing off to his next rehearsal, his next play, and the next stage of his art.

More Stories

Broadway Preview: Lewis Flinn’s Cabaret

Off-Broadway Revew: The Imaginary Invalid

Broadway Review: Call Me Izzy